Notes on Taiwan

Semiconductors, sunsets and hot springs

三年一小反, 五年一大亂

Every three years an uprising, every five a rebellion.

—Xu Zonggan (1796–1866), governor of Taiwan

Earlier this year, I went to Taiwan for two weeks. It was my first time in East Asia.

I received a warm response when I posted my travelogue from South India, so I thought it would be a good idea to also write one for Taiwan. We deemed it to be of enough general interest to run it on The Fitzwilliam instead of my personal blog.

I made sure to have layovers in mainland China on either side of the trip, in Shenzhen and Beijing. They were a fascinating few days in their own right, but I will save my notes about them for a future time when I have, I hope, a longer China trip to write about.

I went to Taiwan to work as an instructor for the Asian Spring Program on Rationality. The title ‘instructor’ is a farce; among other things, the students were only a few years younger than me.1 They were also a great deal more intelligent; an appreciable fraction have medals from competing in international mathematics and science olympiads. Insofar as I can defend my presence there at all, I’m reminded of Steven Pinker’s description of the purpose of nonfiction writing: Write not because you think you are smarter than your audience, but because there is something you have seen that, for whatever reason, they have not yet come across, and you wish to share it with them.

At ASPR, I taught ‘morning classes’ about causal inference and an area of philosophy called anthropic reasoning. I also ran various afternoon and evening activities, including a Miles Davis listening salon, a tutorial for my spaced repetition system, an overview of Newcomb’s problem,2 a Tang dynasty poetry reading,3 a logic puzzle competition, and a workshop about why so many episodes of The Simpsons have covert mathematical interpretations.

People sometimes ask me what these ‘rationality camps’ are actually about. I am reminded of that old quip about how to define mathematics: ratcamp is that which is of interest to ratcampers.

Those of you who read my lecture notes at the time might be wondering why it took me nine months to prepare this travelogue for publication. Concretely, I got massively sidetracked by finishing university, having a job, and other projects. But, at a deeper level, it took me so long to finish this for the same reason I am not more productive in the other spheres of my life: I can’t stop going down Wikipedia rabbit holes about Chinese history.

In preparation for the trip, I read Rebel Island: The Incredible History of Taiwan by Jonathan Clements.4 I found that via Russell Hogg’s podcast, where he often discusses East Asian history and culture. Another recent writer of a Taiwan travelogue is the author of Pimlico Journal, who was a source of helpful recommendations.

I also read Oliver Kim and Jen-Kuan Wang’s excellent paper reassessing the conventional wisdom (popularised by Joe Studwell and others) that land reform was absolutely central to Taiwan’s postwar economic boom. The first draft of this essay contained a gigantic tangent about that, which I partly relegated to Links for February.

For obvious reasons, Taiwan often comes up in the news. I assume that Taiwanese get sick of their home only being brought up by Westerners in the context of Cold War 2.0 and/or thermonuclear annihilation. This is one reason why some of the other travelogues I read rubbed me the wrong way. For my trip, I hoped to surface some of the lesser-appreciated aspects of Taiwan in the West. Here are my notes on that attempt.

Getting to Taiwan

Logistically, travelling to Taiwan is as easy as anywhere I’ve been. Travel to mainland China and to Taiwan is currently visa-free for Irish citizens for 30 and 90 days, respectively.5 The flights are not unreasonably expensive either; now is a good time to visit. It’s much easier for me to go to Taiwan than it is for Chinese citizens, who require a special permit.

This is in contrast to Taiwanese people, who can visit the mainland relatively freely. One of the topics that sometimes comes up on Drum Tower, The Economist’s China podcast, is the efforts of the Chinese Communist Party to sponsor Taiwanese tourism and other cultural efforts aimed at ‘soft reunification’. But, as we will see, the question of how unified China and Taiwan ever were to begin with is a fraught one.

Taipei’s nearest major international airport is in Taoyuan, which is to the southwest of New Taipei City. New Taipei is mostly postwar sprawl, and as such is less interesting than Taipei proper.

Taoyuan Airport is completely bizarre. The gates all have different themes, often including video games or other popular media, such as Hello Kitty. It is explained well in this Instagram video. I waited while sitting in a canoe (!) at a gate themed around Taiwan’s indigenous population.

At first, I was cynical about this, but Taoyuan is just about the only airport I’ve been to that was meaningfully differentiated from the others. The gift shops were also unusually high-quality, and I picked up some nice chopsticks for my friend.

Once I arrived, I had fast internet anywhere I went on the island, with help from an eSIM serviced by Chunghwa Telecom. This is, of course, a far cry from mainland China, where every service essential for navigation and communication has been banned and/or is inaccessible without a VPN.

Demographics and identity

Taiwan has a population of about 23 million. Of those, 97% are Han, which is the ethnic group that makes up around 90% of China itself. Despite this, Taiwan is quite diverse by Chinese standards. People have settled in Taiwan in successive waves from all across China, and it breaks down approximately as follows:

70% Hoklo: Descendants of immigrants from Fujian province, who speak Taiwanese Hokkien. If someone refers to the ‘Taiwanese’ language, they probably mean the Taiwanese dialect of Hokkien.6 Migration from this community picked up in the 17th century.

15% Hakka: People from the Central Plains of China, especially Henan, who speak Hakka. They arrived slightly later than the Hoklo and settled more in the mountainous and interior regions.

12% Wàishěngrén (外省人): ‘Blow-ins’, the descendants of the Nationalist army and their families, who retreated to Taiwan in 1949. This group numbered about 2 million. They are more likely to speak Mandarin and are contrasted with the pre-existing běnshěngrén (本省人) population. You’ll be hearing much more about them later.

2% Indigenous groups: The ethnically Austronesian people who dominated the island until the 17th century, after which they were gradually displaced by Chinese immigrants.

1%: Other.

It is interesting to speak with young Taiwanese about which of these groups, if any, they most identify with. Much like Hong Kong, Taiwan’s history has led many people to selectively exaggerate or downplay certain aspects of their ethnic and cultural heritage. For example, 64% of Taiwanese nationals now identify only as ‘Taiwanese’, as opposed to ‘Taiwanese and Chinese’ or just ‘Chinese’.

Interestingly, everyone I spoke to (Taiwanese and non-Taiwanese) was under the impression that the Wàishěngrén are a much larger group than they actually are. Some people at camp guessed that over half of the Taiwanese are descendants of retreating soldiers from the Chinese Civil War. I assume this is yet another example of how people are terrible at estimating the relative sizes of salient population groups, like how Americans think there are literally 15 times as many Jews as there actually are.

On not speaking Chinese

In Taipei, you can get by only speaking English, but it becomes tougher the more rural you go. About 30% of Taiwanese people speak English to some degree, but fewer than 10% are fluent. The use of English has also been actively promoted by the Taiwanese government through the 2030 Bilingual Nation campaign. This is in contrast with China, which has been putting less emphasis on English in education recently. Proficiency in Mandarin is almost universal, although ~85% of families also speak Taiwanese Hokkien or another dialect at home.

The use of the term ‘dialect’ in China is farcical. As the old saying goes, a language is a dialect with a navy, and the Chinese government has a significant political incentive to downplay linguistic diversity. Mandarin, Hokkien, Cantonese, and Hakka are not mutually intelligible. It is indeed unsurprising that the group which has made up between a third and a fifth of all human beings, depending on the century, speaks many languages.

All of which is preamble to saying: Probably the biggest effect of this trip for me personally was to make it salient how much I really wish I knew how to speak Chinese. Most of the time, when I hear someone tell me about the ostensible benefits they got from learning a language, they justify it with Whorfianisms about how ‘language shapes how you think’ which I think has been convincingly refuted by modern psycholinguistics. But Chinese really seems different. Owing to the censorship, the internet has not necessarily had the same homogenising effect on Chinese people as it has had elsewhere. Even with rapid machine translation, there is an enormous amount that still feels incomprehensible about China without being able to chat with people. It depresses me that it supposedly takes over 2,000 hours for an English speaker to learn Chinese, and it depresses me even more that I would have gotten half of the way there in the time I spent playing Team Fortress 2 as a teenager. On the other hand, the latest generation of AirPods has a real-time translation feature, so it seems like the value of language-learning is falling precipitously.

The Chinese for ‘thank you’ is xièxiè (which to me sounds like ‘sheh sheh’). This is one phrase where Taiwanese have a distinctive pronunciation, and when Nancy Pelosi visited the People’s Republic of China in 2015, she pronounced it in exactly the Taiwanese way, inspiring pearl-clutching and fury from Chinese nationalists online.7 A week in, I was still being self-conscious, and cluelessly saying ‘thank you’ to people who didn’t speak a lick of English. Jinglin Li8 roasted me: “Sam could probably tell you when the Ming dynasty was down to the year, but has been here a week and still hasn’t figured out how to say ‘thank you’.”

I have a bizarrely disproportionate number of Western friends who speak Chinese to a reasonable level of proficiency. I recently had a friend stay over whose last name is ‘Zhang’, who is being helped in brushing up on her Mandarin by her white boyfriend, which is perhaps a sign I’ve been spending too much time in the Bay Area. It is utterly incomprehensible to me how they learned it, and it seems that only complete immersion would work. I have considered when and if my medium-term life goals are achieved – Ireland has abundant housing supply and/or we have aligned AGI, whichever is easier – applying to the Schwarzman Scholarship, and moving to Beijing. (If you feel strongly that this would be a good or a bad idea, email me.)

The great linguist of our friend group, Oisín Morrin, has also been trying to convince us to start a Fitzwilliam Mandarin study club. I’m sure the thought will please those of you bemoaning that our meetups about international trade economics and recreational number theory aren’t niche enough.

Divided by a common language

The first thing I noticed after I arrived in Taipei was that the English language versions of the street names are written confusingly on Google Maps. It seemed that different streets, which I thought represented the same concept or location, were being transliterated differently.

You might innocently ask: ‘Why?’ Like everything about Taiwan, understanding the answer will require a monstrously complicated digression.

It would be great if there were one universally agreed-upon way of phonetically converting the sounds of Chinese into the Roman alphabet. This is helpful for foreigners, who can track when the same concept is being referenced and know approximately how to say it. It also allows Chinese people to type on a Western-style keyboard. It would be impossible to have enough keys to represent all of the thousands of characters in the Chinese writing system, in which one character represents one morpheme.

Since 1958, the main way of doing this has been a system called Hanyu Pinyin.9 There are different tradeoffs with transliteration systems; pinyin was designed primarily to promote literacy within China, and is actually quite unintuitive for English speakers (why are there so many x’s?!).

The creation of Hanyu Pinyin was an example of that rarest thing in history: Chairman Mao actually doing something good. The adoption of pinyin allowed Chinese people to type in a standardised way, and thus the introduction of keyboards and the computer wasn’t complete chaos. If you’ve noticed Chinese names having different spellings in old books (e.g. Mao Tse-tung vs Mao Zedong) and/or containing suspiciously many apostrophes (e.g. T’ang dynasty vs Tang dynasty), it is because the previously dominant romanisation system was Wade-Giles.10 [Edit: I originally gave ‘Peking’ as an example of a Wade-Giles name, but a commenter points out that it comes from an earlier tradition. Using the Wade-Giles rules, ‘Peking’ should be ‘Pei-ching’. While pinyin also uses apostrophes, they mean a different thing; a pinyin apostrophe sometimes disambiguates where a syllable begins, like in Xi’an, while a Wade-Giles apostrophe means that the preceding consonant is aspirated.]

The problem, according to the Taiwanese government, is that pinyin was made by commies. And commies are evil. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) instituted pinyin in the same year as the Great Leap Forward, a man-made famine which led to over 30 million deaths. It would have been deeply embarrassing to admit that, on this one particular issue, Taiwan had something to learn from its bigger neighbour.

My tour guide in Taipei was Juan Vazquez. When he whipped out his phone, I was stunned: the keyboard in Taiwan looks completely different to the keyboard in China. That is because Taiwan still uses the Zhuyin system. The goal of Zhuyin is the same as pinyin, but the symbols are derived from sounds associated with existing Chinese characters, rather than a foreign alphabet:

Zhuyin was introduced in 1918 and was the way that all of China phonetically represented characters until the communists won the Chinese Civil War. However well it might work for typing, a standardised romanisation system is still undeniably helpful. And so, in the 1990s, a new system was developed specifically for Taiwan called Tongyong Pinyin, which became the standard in 2002. This was criticised by many for creating a confusing and inconsistent standard for the benefit of ~2% of total Chinese speakers.

The two main political parties in Taiwan are the right-wing nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) and the left-wing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP).11 Originally, as the self-appointed guardians of Chinese culture, the KMT was reluctant to give up Zhuyin, and opposed the introduction of Tongyong Pinyin. The KMT were the losing side in the Chinese Civil War – which, again, we’ll get to soon – but, ironically, are now the more pro-Beijing party.12 As such, when they came into power in the late 2000s, the KMT abolished Tongyong Pinyin, and switched to Hanyu Pinyin in 2009.

(Ironically, the name ‘Kuomintang’ is itself in Wade-Giles. Some sources will use their Hanyu Pinyin name ‘Guomindang’, which confused me a great deal for the first few hundred pages of Ezra Vogel’s biography of Deng Xiaoping.)

So how does this relate to my trip? Well, names are sticky, and (unlike India!) Taiwan also has a presumption against renamings. The renamings that do occur are often politically motivated. So, when you hover over a location on a Taiwanese map, the name could be in:

Wade-Giles, if it’s an old name that has become iconic and no one wants to change it. ‘Taipei’ is an example; it should be spelt ‘Taibei’, with a b, in pinyin. Nowadays, people also drop the apostrophes and hyphens from writing Wade-Giles names, even though they are an essential part of the system, and if you ignore them, you get an inaccurate impression of how the word is supposed to be pronounced.

Tongyong Pinyin, if the street opened between 2002 and 2009 and/or is in a strongly DPP constituency, e.g. Jhongli District.

Hanyu Pinyin, if the street opened after 2009, and/or is in a strongly KMT constituency.

Some place names mix systems within the same word, e.g. the name ‘Taichung’ mixes Hanyu Pinyin and Wade-Giles.

There are some older romanisation systems, other than Wade-Giles, that have influenced modern spelling. Eventually, I gave up on trying to understand this, because it was getting too complicated.

To translate this into Irish terms: It’s a bit like if, instead of being unable to agree on what we’re supposed to call Derry, we got upset about how ‘Derry’ should be represented in the alphabet for a language that we don’t even speak. The whole thing seems unbelievably petty to me, but I also kind of love it.

My friend was caught out by a Chinese flight website, where you have to type in Taibei, with a ‘b’, to go to Taipei. I assume this bamboozles enough Westerners to significantly hurt their sales, but they do it anyway, because China has political reasons to promote Hanyu Pinyin as the one true romanisation.

But probably the more consequential orthographic difference between Taiwan and the mainland is that the mainland uses ‘simplified’ Chinese writing, while Taiwan uses ‘traditional’. Simplified Chinese is another Mao-era piece of social engineering, this one introduced in 1956. Completely unlike, for example, the marvellous Korean alphabet, Chinese writing is one of the most insanely complicated systems ever designed by humans. Simplified Chinese pared down the number of strokes significantly, with the goal of improving literacy. This also caused lots of characters to merge into one, with the meaning being determined by context. Even if the Taiwanese leadership had agreed with the goals – and there are debates about Simplified Chinese to this day – it would have been politically impossible to switch Taiwan to Simplified.

I saw a child reading a book next to me on a flight from Shenzhen to Taipei, which is when I realised that this is more complicated than I thought. Taiwanese books are read up-to-down and then right-to-left, unlike books published in the mainland, which read left-to-right and then up-to-down. However, if a portion of text contains any English text, such as a brand name, then the entire paragraph will switch to the mainland system, before switching back.

The Generalissimo

You might wonder how I noticed the strange romanisations from the previous section. It’s because, on my first day in Taipei, I started by walking around the Zhongzheng District downtown. It is named after Chiang Kai-shek, who was the leader of the KMT from 1925, and dictator of Taiwan until his death in 1975. If you’re wondering how on earth you could get ‘Zhongzheng’ from that, it is because ‘Chiang Kai-shek’ is the romanisation of his name translated into a completely different language: Cantonese.13 ‘Jiang Zhongzheng’ is the Hanyu Pinyin of his ‘courtesy name’, which is the Chinese tradition of giving men new names (!) when they turn 20. By today’s standards, Chiang’s given name should be spelt ‘Jiang Jieshi’. If you use Wade-Giles but don’t make the strange decision to first translate into Cantonese – a language Chiang didn’t even speak – then you get ‘Chiang Chieh-shih’.

I would not have guessed in a million years that all these names are referring to the same person. In the West, his ubiquitous nickname since the 1920s was ‘The Generalissimo’.

At the heart of the Zhongzheng District is one of Taiwan’s most iconic buildings: The Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall. Underneath, it has a great museum.

Admittedly, having the centrepiece of your city be a giant monument to a dictator sends a questionable message. The square that the memorial is in used to be called Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Square, and then the Democratic Progressive Party changed its name to Liberty Square in 2007. When the KMT got back into power, they restored various symbols associated with Chiang, although never went so far as to change the name of the square back. It is still a Taiwanese culture war to this day. Like Tiananmen Square, but with a happier ending, the most famous student protests for democracy took place on Liberty Square.

Taiwan is one of a kind

What kind of a thing is Taiwan? There are obviously lots of border disputes around the world, and the question of how many countries there are depends on who you ask. Nevertheless, there is a strong case to be made that Taiwan’s status is sui generis. As such, there isn’t really a general principle of international relations that would cause you to take one side or another on its history. Here is the relevant timeline:

1912: The Qing dynasty is overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution, and Sun Yat-sen becomes president of the newly declared Republic of China (RoC).

1916: China descends into chaos, and different provinces come to be ruled by rival warlords.

1924: The Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party form the First United Front to end the Warlord Era.

1937: The KMT and the Communists form the Second United Front, to fight in the Second Sino-Japanese War. Although they despise each other, they hate the Japanese even more. In my opinion, this is a more defensible date to consider as the beginning of World War II than 1939.

1949: Mao Zedong’s communists win the Chinese Civil War, and they declare the new People’s Republic of China (PRC). Chiang Kai-shek and two million refugees retreat to Taiwan, which they insist is temporary and strategic. Chiang claims to be ruling the Republic of China in exile.

1950: The United Kingdom recognises the PRC as a legitimate state, and not just a rebellious province of the RoC. Most countries take much longer.

1971: The PRC is recognised as “the only legitimate representative of China to the United Nations”, and replaces the RoC as a permanent member of the Security Council.14 Taiwan essentially ceases to be considered a country by the international community. The US outwardly opposes this, while behind the scenes, Henry Kissinger is negotiating with Zhou Enlai to shift American support to the PRC.

1979: The United States recognises the PRC, stops recognising the RoC, and opens an embassy in Beijing.

After 1971, many countries were slow to switch their recognition from the RoC to PRC as the ‘true’ China, and some still haven’t done it. Taiwan has a dwindling number of embassies around the world, which is now down to twelve, in Belize, Eswatini, Guatemala, Haiti, Vatican City, the Marshall Islands, Palau, Paraguay, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Tuvalu. A cynic would say that Taiwan bribes tiny island nations with generous foreign aid packages to take policy stances on issues that they don’t actually care about, although there is more nuance to it than that.

Most major countries have a ‘Taipei Representative Office’, which de facto acts like a Taiwanese embassy for the purposes of diplomacy, trade, and so on. But if you change even a single word in its name to remotely insinuate that it actually is an embassy or a consulate, then China will sanction you, as Lithuania has recently discovered. The official policy that almost every Western country subscribes to is ‘One China, Two Systems’, which is the idea that the government in Beijing is the only diplomatically legitimate representative of the Chinese people, but that Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau are governed differently owing to their unique historical circumstances.

Add to this China’s five autonomous regions, thirty autonomous prefectures and one hundred and twenty autonomous counties, and I am losing track of how many systems this ‘One China’ is supposed to have.

One of my closest friends is an economics professor, and he has told me that the single most common complaint he’s gotten in his entire career has come from Chinese students, after he has shown GDP statistics or other graphs which insinuate that Taiwan is a separate country. Even Chinese students at prestigious Western universities get upset about this.

The general norm is that whenever a country has a civil war, we wait a tasteful period of time, and then recognise whichever side won as the legitimate government. It is much rarer for the losing side to continue thriving indefinitely in a defined geographical area, without coming to any formal agreement about partitioning the country. It’s rarer still for that breakaway area to be so clearly superior from the perspective of human flourishing and international development. I think it’s genuinely unclear what one should do in such a situation.

I came across an example of this strangeness in the wild when I was trying to learn how I should refer to Taoyuan – is it a city, county, etc.? Taipei, New Taipei, and Taoyuan are special municipalities (直轄市), which are areas administered directly by the central government. That is one of three categories of national-level jurisdictions, the others being counties and ‘provinces’. Bizarrely, Taiwan is itself considered a province of Taiwan. That is a vestige of the Republic of China’s claim to be the One True China, of which Taiwan is (geographically) only a small part. After Lee Teng-hui’s 精省 (‘streamlining’) reforms of 1998, there is no longer any apparatus for administering these ‘provinces’. That was but one step in the gradual admission that the RoC will never retake the mainland.

The Taiwanese constitution still claims sovereignty over Beijing. This is absurd, but it’s also the third rail of Taiwanese politics: if you touch it, you die. Just about any change in Taiwan’s status could be interpreted as a move toward a declaration of independence and provoke Comrade Xi to invade. As with many things about Taiwan, the current setup is completely crazy. But any change would make things so much worse.

The 2020 redesign of the Taiwanese passport has tried to deflect attention away from these issues with an ingenious diplomatic strategy known as “putting the word Taiwan in a really big font”. If you can’t understand Chinese characters, all you can read is TAIWAN PASSPORT in obnoxiously large text, and ‘Republic of China’ written in a circle that you have to squint to see. The Chinese text only says Republic of China (中華民國).

These kinds of constitutional figleafs are not uncommon: Dublin didn’t formally recognise Northern Ireland as being part of the United Kingdom until 1998.

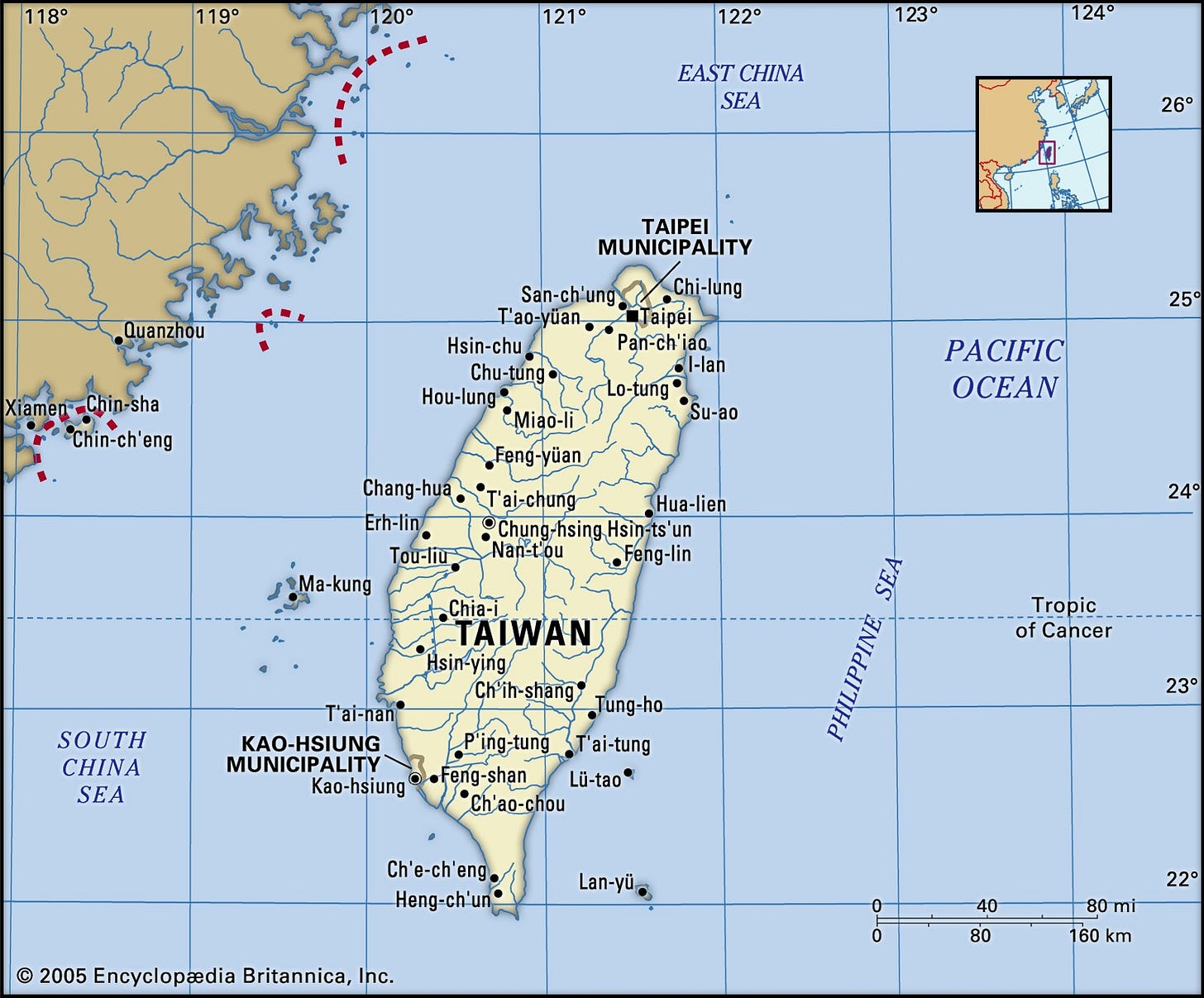

There are some other points of confusion about what exactly constitutes the ‘Republic of China’. For example, the Kinmen Islands and Matsu are controlled by the RoC, but are not part of Taiwan. This is a headache for Taipei, because (a) the population there is much more pro-Beijing, and (b) they are only a few kilometres away from the city of Xiamen on the mainland, and so can easily serve as the basis for an invasion. This actually sort of happened during the Quemoy crisis in 1954, over which the United States Secretary of State was actively drafting plans to nuke China. Believe it or not, the fate of these islands (which I’m confident <0.1% of Americans could identify on a map) was one of the key issues discussed in the 1960 presidential debates between Richard Nixon and John F Kennedy. While the declining calibre of presidential debates has been widely noticed, could you even imagine a presidential candidate today discussing the geostrategic significance of Fujian province?15

I tried to visit the Kinmen Islands to see for myself, but unfortunately had to cut my trip short to go home and take an exam.

Depending on how pedantic you want to be, the Republic of China inherited many border disputes by purporting to be the successor to the Qing, but they don’t recognise the subsequent bilateral treaties with the People’s Republic resolving many of said disputes. This leads us to an amazing piece of pub quiz trivia that the place with the largest number of disputed borders in the entire world is… Taiwan! Strictly speaking, the Republic of China doesn’t even recognise the existence of Mongolia (?).

Sun Yat-sen

I mentioned that Sun Yat-sen16 was the first president of post-imperial China. He only lasted a few months before being ousted in a deal with a northern general who still had the loyalty of much of the military. Sun was the founder of the Kuomintang, the ancestor of today’s political party.

After Sun Yat-sen died of cancer in 1925, there was no longer any widely respected moderating figure between the communists and the KMT. Two years later, Chiang began brutally purging leftists in the April 12 Incident. This de facto ended the First United Front and was the beginning of the Chinese Civil War. The tragic irony is that previously, the Kuomintang was intentionally ideologically diverse and contained many members sympathetic to communism. But they were an obstacle to Chiang's centralising power.

Since he died before that rift, Sun Yat-sen is basically the only historical figure that nationalists, communists, Chinese and Taiwanese people all agree was good. That is true to this day; Sun Yat-sen is widely commemorated in both polities. Sun is on the $10 coin for the New Taiwan dollar. How many cases do we have in history of two rival regimes, with opposite ideologies, both claiming the same person as their founding figure?

I was in Taiwan not long after the Lunar New Year. I was shocked to see that the new year banners didn’t say 2025; they were in the Minguo calendar, in which the formation of the Republic of China in 1912 is considered Year 1.

I tried to go inside the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, but it was closed for renovations. It’s not as cool as the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, but it’s still cool.

Attitudes to colonialism

One of the topics where I was keen to sample the views of young people was colonialism.

The first Europeans to settle in Taiwan were from the Dutch East India Company, who established a base there in 1624. The Portuguese had been aware of its existence since the 16th century, and they called it Ilha Formosa (‘beautiful island’). Formosa has been a beloved moniker for Taiwan ever since.

At that time, the population of the island was dominated by the indigenous population. Then, in 1662, a general for the recently overthrown Ming dynasty called Koxinga kicked out the Dutch East India Company and established an ethnically Han state in Taiwan.17

This is remarkable for two reasons. First, it means that, in some sense, Taiwan was ruled by white people before it was ruled by Chinese people. Second, the reason why Koxinga was interested in Taiwan was so that it could be a successor state to the Ming, and eventually retake the mainland. After a civil war that might have killed a third of the entire population of China, the Ming fell to ethnic Manchu invaders in 1644, which was the beginning of the Qing dynasty.18

If I had a nickel for every time that Taiwan has claimed to be the rightful successor of a deposed Chinese regime, which insisted that Taiwan was only a rebellious province, in a way that became a geopolitical flashpoint threatening Western interests because of the region’s trade and control over strategic resources… I would have two nickels. But it’s weird that it happened twice!

Of course, the much more salient example of colonialism to Taiwanese people is Japan. Taiwan was a Japanese colony from 1895 to 1945. Taiwan was among the spoils of victory that went to Japan after the First Sino-Japanese War. I was interested in how much ill-feeling there still exists toward Japan today. Are people still mad about the Japanese occupation, the way they are in Korea?

My sense was that it’s much more muted. For one thing, the possibility of being de facto ‘colonised’ by mainland China is much more salient. For another, there is an acknowledgement of the Japanese role in boosting infrastructure and agricultural productivity, in a way that arguably laid the foundation for their subsequent success. For example, the engineer Yoishi Hatta is so respected for his role in creating Taiwan’s irrigation system that he has literally become a god in Taiwanese folk religion.19 The Japanese were also responsible for introducing many public health and sanitation measures to the island for the first time. And in recent times, Japan hasn’t done as much to pointlessly damage its relationship with Taiwan as it has with Korea, the way, e.g. Abe Shinzo did to Korea by visiting Yasukuni Shrine.20

Postage stamps

A quirk of Taiwan’s history is that there was a 151-day gap between the Qing dynasty giving up on Taiwan in 1894, and the Japanese taking control. The government declared independence in that period, leading to the creation of the Republic of Formosa.

What is much less widely known is that the Republic of Formosa was financed by the brief mania in the late 19th century for postage stamps. Rare postal stamps saw extraordinary increases in value around this time, and the new cash-strapped Formosan government started selling off stamps with their national symbol of the tiger. The records aren’t good enough to know how big a deal this was as a fraction of government expenditures, but I guess the closest modern equivalent is if an independence movement was funded by issuing bored app NFTs.

A few years ago, the National Postal Museum in Tainan – which was the capital of Formosa – started selling some of the original Republic of Formosa stamps. One of my missions while I was in Taiwan was to buy one of the original Formosa stamps. I thought it would be a really cool gift; who wouldn’t want to own the speculative asset class that financed Taiwan’s only brief existence as an independent country?

Alas, I wasn’t able to make it to Tainan in time to confirm the rumours I saw online. But after much perusal in the world of philately, I have now bought two of these stamps. I have pinned down a book that I think will help me identify whether they are genuine Republic of Formosa stamps, but it’s out-of-print and untranslated. I’ve also been unable to get in contact with either Jonathan Clements or Russell Hogg. Long shot, but if any of you have expertise in the late Qing postal system and want to go on a side quest with me, please email me.

Mazu the sea goddess

For many reasons, organised religion never really caught on in China. But of the forms of folk religion practised in Taiwan, the most famous example is probably worship of Mazu the sea goddess. Different aspects of Mazu worship have been incorporated into Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism. My taxi driver seemed impressed when I was able to identify the Mazu statue 10 minutes out from the venue where I was staying. We drove past it on my ‘rest day’ halfway through my trip, in which staff were encouraged to leave camp and travel around a bit to avoid burnout.

Two years ago, Drum Tower ran a story about the Taiwanese government encouraging belief in Mazu as part of a campaign to encourage a more distinctively Taiwanese identity in contrast with the mainland.

Mazu is so salient in Taiwan because, when the ethnic Han population first came to work on the Dutch colony 400 years ago, they prayed to Mazu because so many of their ships had been destroyed by stormy weather in the strait. In Hakka and Hokkien, the Taiwan Strait is called ‘Black Ditch’, in reference to how perilous it can be to cross. This is crucial context for understanding the difficulties that would be faced, hypothetically, by an amphibious invasion of Taiwan.

If there were a Taiwanese version of The Fitzwilliam (is there?), I’d be interested to read an equivalent of our essay about Protestant magic. What are the origins of the way these folk myths are currently practised? How have they influenced the way that Taiwanese youth think about themselves? Are many of the details surprisingly recent fabrications?

Other cultural differences

To the casual observer, Taiwanese culture is an even mix between Japanese and Chinese. The Taiwanese seem to have inherited strong norms of cleanliness and politeness. My friend who went to Taiwan last year told me about how he couldn’t get his eSIM or payments working, and so a stranger took 40 minutes out of his day to bring him to a phone shop and then to an ATM to make sure there were no issues. In China, it felt more like every man was for himself.

Nowhere is the Japaneseness of Taiwan more apparent than in the queuing culture. I’ve never been to Hong Kong, but I’m told by those who have that the difference between the style of queuing on the HK side compared to the chaotic Shenzhen side is readily apparent; among other things, the departing British imparted their love of orderly queuing. Something similar seems to have happened in Taiwan.

In Taiwan, it also goes without saying that you’re not supposed to wear shoes indoors (always a culture clash when an Irish person hangs out with East Asians). At our venue, the shoes lived in the ‘shoe territory’, for no rack would be sufficient to contain us. There was a designated ‘shoe bandit’ tasked with recovering shoes outside the territory, and causing mischief to the person responsible. As a result, I went over 48 hours once without putting on a pair of shoes, which is probably the longest I ever have since childhood.

After his extensive travels, one of Matt Lakeman’s hypotheses about human culture is that politeness and friendliness are negatively correlated. In Japan, people have impeccable manners, but you can live there for years, speak the language, and still be treated like a complete outsider. In Sub-Saharan Africa, you will often have random people shout rude stuff at you on the street – I speak from some experience – but it also won’t be long before someone offers to let you stay in their home, or otherwise engage in a genuinely costly signal out of warmth to you. I don’t think one point on the spectrum is inherently superior to another, although I think it does tell us something about why quiet noise-sensitive nerds like East Asia so much.

Martial law and democracy

As late as the 1970s, Chiang Kai-shek was still outwardly professing a desire to raise an army and retake the mainland. His one-party rule in Taiwan was justified on the basis of martial law being in place, a holdover from the Chinese Civil War.

Chiang died of natural causes in 1975. The vice president at the time took over, but it was widely understood that Chiang’s son, Chiang Ching-kuo, held the real power. Chiang the Younger became president in 1978, but was less authoritarian than his dad. Chiang Ching-kuo lifted martial law in 1987, which allowed for opposition parties. Until it was overtaken by Syria, Taiwan held the unenviable record of the longest amount of time a place had ever been ruled by the military. The Democratic Progressive Party had previously been an underground organisation, but the KMT had eventually lost the energy to continue suppressing them. In 1991, Chiang’s successor, Lee Teng-hui, ended the ‘Period of National Mobilisation for Suppression of the Communist Rebellion’, which had justified many expansions in state power since 1948. This was essentially a formal admission that the civil war was over, and that a democratic government needed a constitutional basis. Taiwan had its first free and fair parliamentary elections the following year. From what I could tell, President Lee was genuinely moved by the scale of student protests for democracy, and is more responsible than anyone else for turning Taiwan from a dictatorship into a liberal democracy. From the Chinese nationalist perspective, Lee got softer and softer with time, and he eventually resigned from the Kuomintang in 2001.

The most famous of the pro-democracy activists of the 1980s was Nylon Cheng. He published a dissident magazine and commemorated historical events whose existence was censored by the Kuomintang, such as the 228 Incident.21 When a warrant was issued for his arrest in 1989, he barricaded himself in his office and self-immolated. You can now visit his remains in northern Taipei, or see a reconstruction (as I did) in the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall:

Cooking your own food is a policy failure

Here is a thought I have on a daily basis: Why aren’t there more intermediate options between eating in a sit-down restaurant, and cooking your own meals?

I realise this is going to sound incredibly naive, but: Why do you even save money by cooking your own food? Shouldn’t there be massive economies of scale in cooking larger quantities? And shouldn’t some people be naturally more skilful and efficient at it than others? How can it possibly make any sense for a skilled worker to spend hours in a day procuring food, when it is so clearly not to their comparative advantage?

There is a magical place with plentiful such options, and it’s called Taiwan. In Taiwan, you can affordably eat out for practically all meals, and they will consistently be delicious. This is despite the fact that GDP per capita in Taiwan is $33,000 – it’s richer than Spain!

One of the reasons why it can be so cheap is that many of the stalls or buildings you will order food from are not full-time restaurants. A Taiwanese grandmother might earn some extra income on the side by cooking noodles for a few hours in the afternoon.

Abi Olvera recently wrote about how America could easily have such businesses, but zoning makes it illegal. The partial exceptions that exist, such as food trucks, are bedevilled by permitting and regulation, such as the legal requirement that every food business have at least three sinks (?). The Anglosphere system of land use regulation that tries to shoehorn specific uses into specific plots of land is a bad fit for the Taiwanese market. Also, fixed capital and licensing costs for food and beverage businesses in the West have been creeping up for decades. In Japan, which also has affordable, delicious food despite high labour and land costs, you can cover all the fixed costs to open a tiny restaurant for $2,000.22

Whenever this contrast is brought up in Western policy conversations, you hear the usual hysterics about how any loosening in safety regulation would be catastrophic for health. But despite its much more permissive system, in most years, Taiwan doesn’t record a single death from food poisoning. We have regulated out of existence a large category of human social and culinary life, for possibly non-existent benefits, and… nobody seems to care?

Putting aside political rants, another reason why you might be particularly keen on eating out in Taiwan is that food gets mouldy remarkably quickly. It’s hot, humid, and historically a breeding environment for disease. In Taipei, I met up with Lily Ottinger, an American woman who has lived there for three years. She is the producer of the ChinaTalk podcast. When I asked her about the biggest cultural differences between her and her Taiwanese husband, the first thing that came to mind was that Taiwanese people eat popcorn with a spoon. They also eat Doritos with chopsticks, and take pills in such a way that avoids them ever coming in contact with skin. Taiwanese people also freeze their compostable waste (!) before bringing it to be collected. Perhaps as a result, being a bin collector seems like a relatively prestigious profession in Taiwan. Juan tells me he’s never met a Taiwanese bin collector who doesn’t speak good English. It would be interesting if Taiwan is a case of food safety regulation being superfluous, because the cultural norms around it are already so strong.

My first lunch in Taipei was in 豐盛食堂, a restaurant with no English name and no menus, where the day’s food is printed on movable wood blocks. I have no idea what anything was called, but it was amazing.

I get dehydrated easily, and generally am known among my friends for drinking large quantities of water with most meals. It’s not unusual for the only drink at a Taiwanese meal to be tea. It’s possible I drank more tea, especially red oolong, in two weeks in Taiwan than in my entire life up until that point. When Juan asked for water with lunch in a restaurant recently, the staff found it to be such an odd request that they brought it to him in a bowl, since they didn’t own any glasses.23 When you do get water, it’s warm. I could live the entire rest of my life in East Asia, and I would never stop finding that unpleasant.

When I was younger, my travel to more ‘exotic’ locations was limited by my severe food allergies – which I have, happily, largely grown out of. Still, an allergy to peanuts remains, and apparently, the Chinese for ‘I am allergic to peanuts’ is ‘我对花生过敏’. I still have a photo of this translation favourited in my photos app, since I had to show it in so many restaurants.24 The fact that I’m a vegetarian and allergic to peanuts, and still love Chinese food as much as I do, is a testament to how excellent it is.

It’s sad that most Westerners only get exposed to (a certain inauthentic interpretation of) Cantonese food. Chinese food is extraordinarily diverse, arguably more diverse than all European food combined. My favourite type is Sichuanese, but Yunnan province and its use of mushrooms is also extraordinary. In Taiwan, a lot of the food comes from Fujian and from the colonial influence of Japan (you will see a lot more bento and sushi than you would in China). The national dish is beef noodle soup (牛肉麵).

But if you count drinks, Taiwan’s most successful culinary export is probably bubble tea. It’s also called boba, which is based on Taiwanese slang for ‘big breasts’ (!). Bubble tea is a good example of manufactured Taiwanese traditions. On the Canadian version of Dragon’s Den, a company selling bubble tea recently got in trouble for allegedly culturally appropriating from Taiwan, despite the fact that boba was invented in the late 1980s.

Sue me, but I prefer high-end Chinese food in the West to Chinese food in China – precisely because it is more likely to be vegetarian. A lot of the time, my options were fairly limited. One of the stranger experiences of my life was participating in a two-hour podcast with Tyler Cowen specifically about Chinese food, so if you are interested in more of my thoughts on this issue, I would direct you there. In our conversation, Dan Wang bemoaned the ‘hotpotification’ of the subtle glories of Chinese cuisine. He may be saddened to learn that by far the most popular dinner among the students was on hotpot night. And the most popular drink, of course, was bubble tea.

Baseball

While wandering around Taipei with Juan and Lily, I learned something surprising: Taiwanese people are obsessed with baseball. While it is popular in parts of the Caribbean, I was unaware that any other region of the world cared at all about baseball.

In Taipei 101, formerly the world’s tallest building, the observation deck is now the Taiwan Baseball Hall of Fame. One of the things Taipei 101 is famous for is its tuned mass damper: it has a gigantic pendulum inside, which dissipates the force from earthquakes and prevents the building from collapsing. On the mass damper, they were projecting a highlight reel from the career of Shohei Ohtani, who… is Japanese. Like Scottish football, the Taiwanese passion for baseball runs ahead of performance.

As you might expect, Taipei 101 is a tourist trap, but I had such limited time there that I paid for the view anyway. It is right near Xiangshan (‘elephant mountain’), a popular hiking spot. One of the coolest things about Taipei is that, because of its hilliness and inhospitable building conditions, skyscrapers are a half an hour walk away from what is basically jungle. That also means the surfaces are really mossy, which gives everything a futuristic post-apocalyptic feel.

How Juan ended up in Taipei is itself a funny story: He was at ASPR the previous year, during which he found out that he’d have to move out of his flat in Dublin. He liked Taiwan so much that he decided he might as well stay to work remotely. I am not sure the students were aware that “permanent relocation to Taipei” was one of the possible outcomes of the programme. When I was there, he was living with a group of exclusively Mongolian women – is it offensive to call them a ‘horde’? – whose house party I failed to procure an invite to.

The indigenous population

Most of the time I was in Taiwan, I was staying in an area primarily inhabited by the Atayal indigenous group. With all the intermarriage there has been, I was not able to visually distinguish them from Han Chinese. I saw a young Atayal boy in a village I hiked to, who was so bored that he was setting beer bottles on fire.

If you go back far enough, all Austronesian people originally came from Taiwan. The expansion of humans out from Taiwan to the Philippines and beyond started around 4000 BCE. That also means that all Austronesian languages (Malay, Tagalog, Maori, etc.) are descended from a proto-language spoken in Taiwan. Of the 10 branches of the Austronesian language family, all but one are found exclusively in Taiwan. Most of that diversity has gone extinct in practice, as the indigenous population was assimilated into speaking Mandarin. The surviving languages, such as Ataya,l are mostly spoken in mountainous areas and other places far from the administrative arm of the state.

So, from the perspective of anthropology and historical linguistics, Taiwan’s influence on the world has been gigantic. I’m not sure if many Chinese people realise that Taiwan was the gateway by which humans first reached much of the Pacific, from New Zealand to Madagascar.

But what most struck me is how similar the imagery around Taiwan’s native population is to that of Native Americans. As with baseball, Taiwan is conspicuously pro-America. And as with the gate at Taoyuan Airport, Taiwan’s relationship with its native population has borrowed from the ‘cowboys and Indians’ aesthetic, despite that making no geographical or historical sense.

Interestingly, the area where I was staying was strongly pro-Kuomintang. In fact, indigenous peoples are considered a core voting bloc for the KMT, despite the fact that they were responsible for forcibly wiping out much of their language and culture under martial law. Some local villagers claimed to us that the DPP government had closed the only school in the area, because they thought they wouldn’t vote for them anyway.

Semiconductors

After WWII, Taiwan very successfully rose up the value chain in an export-oriented development strategy. Before it was known for semiconductors, one of the main reasons Americans would know about Taiwan was as the source of their Christmas decorations. On the plane to Taiwan, I was reading Ezra Vogel’s collected essays about the South Korean dictator Park Chung-hee. The similarities with Chiang Kai-shek are striking. Both countries experienced remarkable growth pursuing similar economic strategies over the same time period, and then peacefully transitioned to democracy within a few years of each other. In both cases, the places were subsequently led by their children, and the dictator in question has a complicated legacy today because their regime had many undeniable successes. South Korea seems like a much better mental model for understanding recent Taiwanese history than mainland China.

Within Taiwan’s economic strategy, one of the most fateful decisions was the establishment of the Industrial Technology Research Institute in 1973. The purpose of ITRI was to attract foreign direct investment and incubate startups with the help of overseas talent. In the 1980s, a former executive and semiconductor engineer from Texas Instruments called Morris Chang was recruited to lead it. Chang was born in Ningbo, China, in 1931. He left ITRI after a year, but ended up founding one of its spinoffs: the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). Today, TSMC is quite possibly the most important company in the world.

Up until 2018, TSMC dominated the semiconductor industry because of its high volume and great unit economics. But since then, neither China nor the US have been able to replicate the most advanced chip designs produced by Taiwan. There are perennial rumours that the TSMC fabs are boobytrapped, and would be sabotaged in the event of an invasion so that China couldn’t use them. A monopoly on the most advanced chips could give China a decisive military advantage.

In Situational Awareness, Leopold Aschenbrenner has a line about how the fact that Taiwan ended up as the global frontier in production for such a geopolitically significant good is about as insane as if, during the Cold War, the majority of the world’s uranium deposits had coincidentally been in West Berlin. It is scarcely believable that this is the world we ended up in.

For a recent meetup of my reading group, we discussed Karina Bao’s bootleg translation of The Autobiography of Morris Chang. The first volume was published in 1998, and then the second volume – twice as long! – was published in November last year. Neither volume has been officially translated from traditional Chinese into English (hence the bootleggery).

Morris Chang is a national hero in Taiwan, and his autobiography is genuinely extremely interesting. He is still alive and active in Taiwanese public life, aged 94. You can even watch his recent appearance on the Acquired podcast.25 If I go to Taiwan again, I would like to visit the TSMC Museum of Innovation. I am told it consists mostly of bizarre hero-worship of Morris Chang.

The former president of Taiwan, Tsai Ing-wen, famously called TSMC the ‘silicon shield’. There is a widespread sense that TSMC, and quite possibly Morris Chang personally, has prevented a Chinese invasion.

My visit to Taiwan provided me with no additional insight into the semiconductor industry, or anything else about geopolitics, really. For obvious reasons, semiconductor companies are not inclined to give tours. But Morris Chang’s autobiography can be found in all good Taiwanese bookshops:

The mood in Taiwan

The mood I sensed in Taiwan was gloomy. The Taiwanese I talked to were desperate to get green cards to move to the United States. There is a major culture of sending your children abroad for university, so that it will be easier for them to emigrate subsequently. If you’re a male with only a Taiwanese passport when shit hits the fan, you are definitely getting drafted.

Possibly related to this, the total fertility rate in Taiwan is an abysmal 0.87, compared to mainland China’s 1.2.26 Taiwan has tried the usual pro-natalist policies for a greying East Asian nation, to minimal effect.

Taiwan is noticeably more chill than the rest of East Asia. Lily said that when her Korean friends visit, they find it much easier to relax, and don’t feel (for example) oppressively high beauty standards. Even in the luxury shopping centre in Taipei, everyone is wearing tracksuit bottoms and t-shirts. I could imagine myself living in Taipei and being somewhat accepted. There are lots of tourists, it’s not unusual to see non-Asian people, and nobody stops or stares the way they do in China.

The explanation I heard for this equanimity is that Taiwanese people are so used to worrying about their continued existence that they don’t have the mental effort to also worry about day-to-day interactions. But I worry this is an over-interpretation. I heard someone say that the reason why Taiwan’s large airport is in Taoyuan, with only a small one (Songshan) in the city, is to make it more difficult for the Chinese to land planes in Taipei in the event of an invasion. But, for various reasons, I now think this is an urban legend. Having one large airport outside a city, and then a small one centrally for VIPs, shorter flights, or military, is a very common pattern! A lot of things in Taiwan are related to being a small island militarily threatened by its much larger neighbour. But not everything.

The omnipresent force of 7-Eleven

Everybody knows that Western brands have penetrated deeply into the East Asian market. Walking around, you see a lot of Starbucks and McDonald’s. But the sheer dominance of the supermarket chain 7-Eleven is extraordinary. I think I literally never left the line of sight of a 7-Eleven the entire time I was in Taipei.

In America, a 7-Eleven is a horrible ‘convenience store’ that sells junk food. But in Taiwan, they’re actually really nice, and sell delicious takeaway and microwavable meals (which you can heat up there). Despite having started in Texas, 7-Eleven is now owned by a Japanese parent company, although it has much less of a presence there.

7-Eleven is so important in Taiwan that it has unofficially become a quasi-governmental organisation. 7-Elevens stay open 24/7, including during hurricanes and other natural disasters. There is an (entirely believable!) urban legend that 7-Eleven has officially been designated as part of the ‘national infrastructure’. A large fraction of the population now pays their bills, prints documents, picks up packages, accesses banking, and buys their phone and mobile data from their local 7-Eleven. They are also just about the only place where you can find a bin. Without them, the nation would grind to a halt.

Hot springs

On my second-to-last day, I greatly enjoyed my visit to the Luofo Hot Springs, which has a great view of the mountains on each side. It was pretty much the perfect choice of decompression activity for a group of people who obviously like each other, but had just spent two weeks living in a confined space, followed by a brutally honest feedback session. I have no idea if alternating between boiling hot and freezing cold water is actually good for you physiologically, but it feels good for the soul.

Juan keeps running into and befriending people at the hot springs whose jobs sound ridiculously important to the global semiconductor supply chain, so I think Karina and I need to pay them another visit. The hot springs are another example of both China and Taiwan seeming like nice places to be old. I was smiling at friendly old people in Daan Park with their friends, who were playing mahjong, singing, practising tai-chi, and so on. They all had remarkably little self-consciousness. In contrast, in the West, it seems like we have totally failed to provide social institutions for the elderly to remain socially and physically active.

The National Palace Museum

On my last day in Taipei, I visited what has become my favourite museum in the world: the National Palace Museum. It is where the historical artefacts are stored that Chiang’s retreating army brought to Taiwan in 1949 for ‘safekeeping’. As such, it contains some of the greatest cultural treasures from all over China.

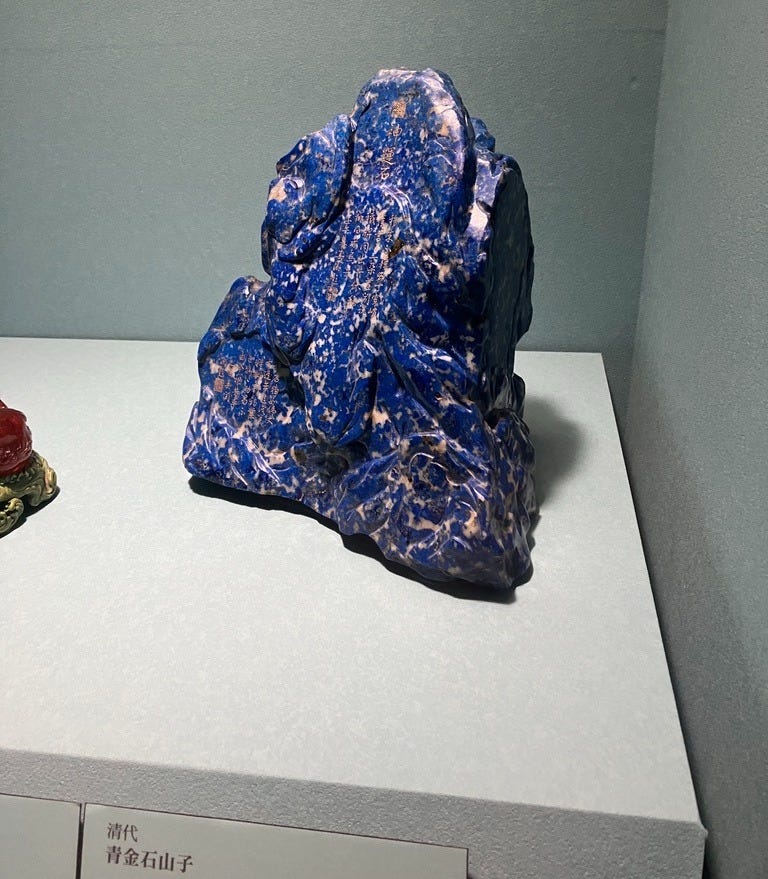

The most famous piece (the Jadeite Cabbage) wasn’t on display when I was there, but I did see the Meat-Shaped Stone, which is an uncanny jasper sculpture from the Qing dynasty:

Chiang made many of the cynical decisions you might expect of what to bring with him: Thousands of families were bereaved because of the alleged lack of space on ships to Taiwan, but there was enough space for the confiscated jewellery of anyone accused of being a leftist (you can see chapter eight of Rebel Island for more detail about this). The National Palace Museum opened in 1965, the year before the madness of the Cultural Revolution broke out on the mainland. This was a major propaganda coup, framing the KMT as the guardians of Chinese culture and tradition.

The National Palace Museum is, fittingly enough, located right next to the Ministry of Defence.

My favourite pieces there were the jades, but there are incredible bronze sculptures and ceramics. I also loved the inkstone room. Inkstones are a tool for grinding solid ink into liquid for use in Chinese calligraphy, and creating inkstones itself is an art form. In particular, we got to see the famous inkstone collection of Mi Fu, a calligrapher from the Song dynasty.

Ancient Chinese history gets murky before the Spring and Autumn Period (8th to 5th century BCE). That came before the Warring States Period, which was itself before the Qin dynasty unified China for the first time. That means that many of the objects in the NPM collection are attributed to dynasties that might be fictional.

I went to the NPM with Jinglin, who, like all rebellious children of Chinese immigrants, knows nothing about Chinese history. She spent most of the day asking me basic questions, but, like most zoomers, I found it difficult to hold her attention.

From the landscape painting collection, I spent most of my time looking into the Qing orthodox school. Within that tradition, the most famous painters are called the ‘four kings’, which is a joke because they all coincidentally share the surname Wang (which means king). Like many people, I’ve long wondered why Chinese names come from such a concentrated distribution. It’s not quite as extreme as Korea, where 20% of the entire peninsula is called Kim, but it seems to be so concentrated to the point of being actively inconvenient for the purposes of unambiguously identifying individuals. How many people in America must be called ‘Kevin Wang’? What you will usually hear from Chinese people when you ask about this is that almost all Chinese names supposedly derive from an original set of eight clan names in ancient China. However, modern versions of Chinese surnames relate to these original clan names in a highly non-trivial branching structure that I eventually gave up on trying to understand.

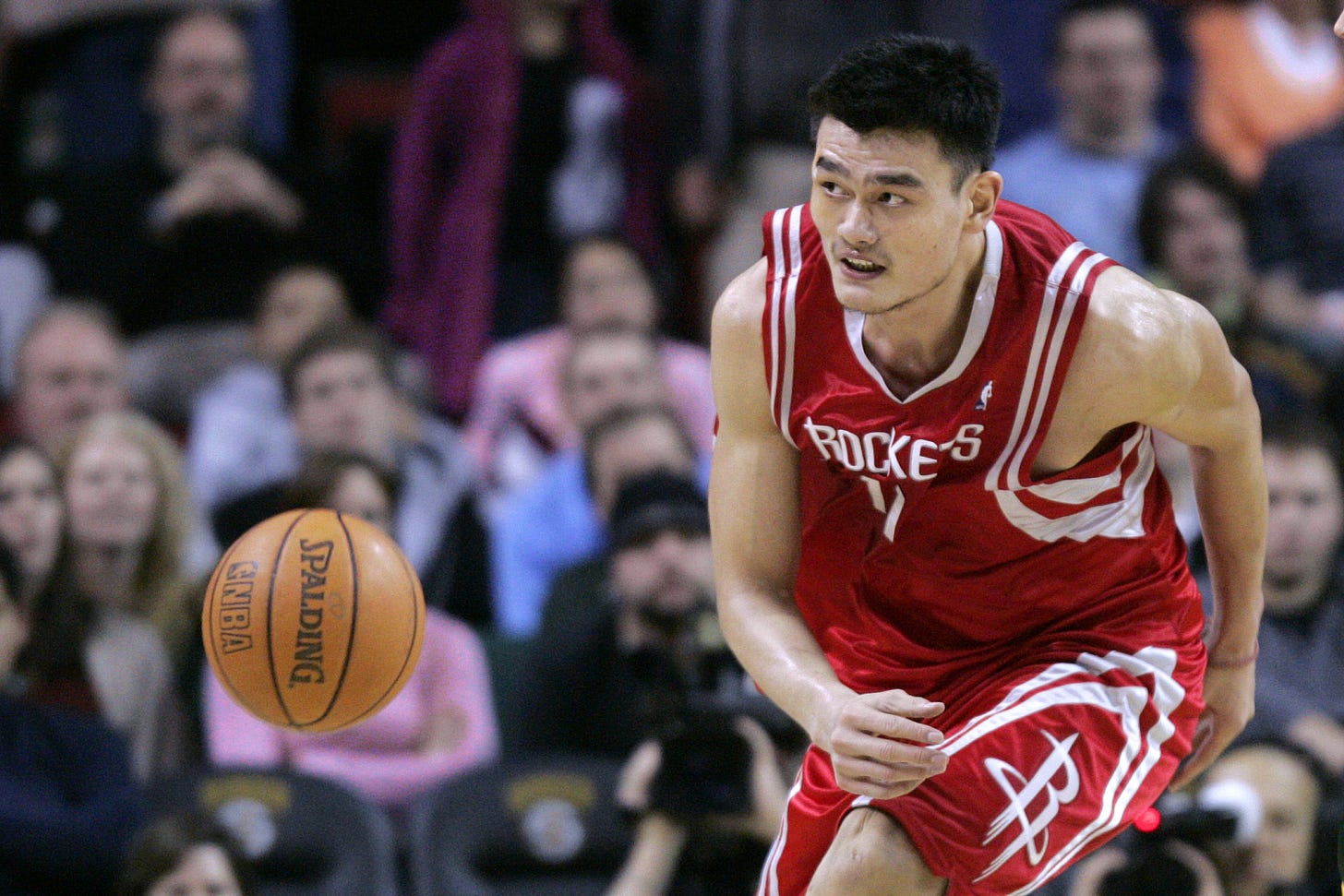

Interestingly, one of the few people to have a name which comes directly from the Eight Great Surnames is the basketball player Yao Ming. There is something poetic about the culmination of the development of the ancient Chinese clan system being to become a millionaire businessman in America.

There was also an exhibit of artefacts related to The Dream of the Red Chamber, which probably few people in the West have heard of, despite it being the sixth most widely read book in human history. In principle, it’s the kind of book I would like to have read, but it’s so absurdly long and complicated that even figuring out how long a translation is supposed to be is an active area of debate. You can also watch the 27-hour TV adaptation, which is honestly on the shorter side by the standards of adaptations of Chinese classics.

Between European and Japanese imperialism, and the convulsions of the 20th century, it’s something of a miracle that China or Taiwan still have any historical artefacts at all. Their preservation was only possible through an elaborate network of smuggling and heroic museum curators.

The core of the collection was evacuated from the Forbidden City in Beijing in the 1930s and 40s. It is basically the Qing court’s collection, and the selection of artefacts reflects their view of the world. I noticed that many of the objects bore the signature of the Qianlong Emperor, one of the most significant of the Qing rulers. He was the one who famously rejected the idea of trade with Britain under the Macartney Mission, saying that China had no need for British goods, and that they wouldn’t impress a Chinese schoolchild. At that time, the pointless gizmos invented in Britain included ‘the steam engine’, so this was yet another self-own by the Qing.

Same-sex marriage

In 2019, the DPP government under Tsai Ing-wen legalised gay marriage. Until the recent decision by Thailand, Taiwan was the only place in Asia where same-sex couples could get married.27 Yet another reminder of how unlikely and precious Taiwan’s existence is.

When he found out that I was going to Taiwan, my cattiest gay friend messaged to encourage me to visit the LGBT neighbourhood in Taipei, saying that “They like white boys”. Alas, for me, that was not competitive with spending more time in the museum, but it reminded me of a hilarious tweet from a few years ago when someone accidentally (?) flew the post-1912 Republic of China flag in the San Francisco Pride Parade. Gays against the Qing dynasty??

Night markets

In case the National Palace Museum was too cultured, that night my friends and I engaged in some debauchery at the Raohe Street Night Market, which I was told is less touristy than the Ningxia Night Market. We also united with a Czech engineer with whom I was in a WhatsApp group, who had clearly been looking for any excuse to go to Taiwan.

Mostly, it was disappointingly repetitive, although there was a cool temple at the end. We did have some bizarre interactions, including briefly appearing on the livestream of a Taiwanese sex worker (by accident!).

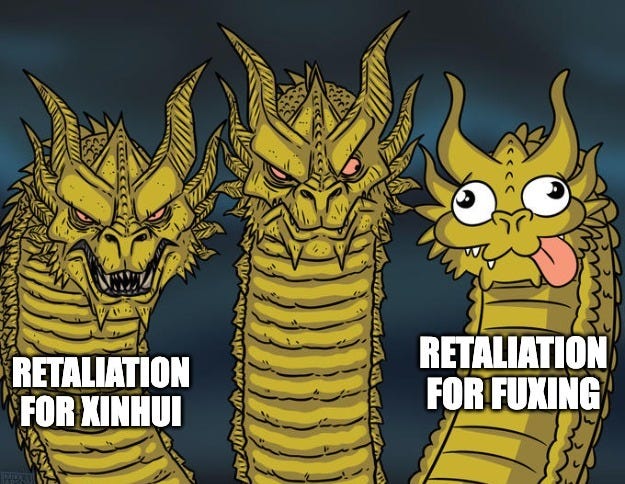

The highlight was my friend getting his astrological fortunes read by some old Taiwanese ladies. The first turned him away because, supposedly, it’s impossible to read the fortune of someone without a Chinese name. The other soothsayer had a more flexible policy. Everything she said was a vague platitude about how he will soon find love or face difficulties. Everything, that is, until her demeanour changed completely, and she made one ominous final comment, which translated to “The retaliation for Xinhui will be stronger than the retaliation for Fuxing!”

I still have no idea what that means.

The night markets were the last thing I did before flying to the UK the next morning. The flights were smooth, but my immune system was run down and I caught the flu. Once I was home, I spent the next 1.5 days in a state of semi-consciousness, while having a terrible fever dream in which my family was being tortured in the Cultural Revolution.

I can only hope I showed Taiwan the proper respect, and I was not being cursed by the retaliation for Xinhui. I hope Formosa will have me back many more times.

Sam Enright is editor-in-chief of The Fitzwilliam, and Innovation Policy Lead at Progress Ireland. You can follow him on Twitter here or read his personal blog here.

I later discovered that most of the students were under the impression that I was in my late 20s or even 30. But there are other events where people consistently underestimate my age; context matters a lot!

The students and staff were mostly one-boxers. Galaxy-brained alternatives to causal decision theory seem to be more common among ‘rationalists’ than professional philosophers.

In which I would read in English and my friend in Chinese, and we would compare. I lament that Chinese poetry is so untranslatable, but that was partly the point. I enjoyed Michael Wood’s book about Du Fu, and, as I wrote about before, found his rendering of Chunwang to be very moving.

This was also where I found the quote with which I began this piece.

At the time I went, China’s policy was said to be in place until Dec 31st 2025. It has recently been extended until the end of 2026.

There are a bewildering variety of different languages in Fujian. For instance, the endangered language of Fuzhounese is spoken more in the north, and Hokkien in the south. The scales remain mind-boggling: in China, the ‘endangered’ languages are still spoken by ten million people. This brings an extra poignance to Yu Ming is Ainm Dom.

See Rebel Island, page 314.

Not to be confused with the ringleader for the Fengtian clique. To the best of my knowledge, Jinglin is just a normal tech girlie in the Bay Area, and doesn’t hold specific views on Japanese involvement in the Warlord Era.

At earlier points in Chinese history, some liberals – and allegedly Mao himself on one occasion – flirted with the idea of abolishing the character system entirely, and switching Chinese to the English alphabet. I briefly mentioned earlier language reform efforts in China as they pertained to the New Culture Movement in my talk at the Bertrand Russell conference this year.

You can listen to the recent China History Podcast episodes about the lives of Messrs Wade and Giles, the British sinologists who came up with this system.

The KMT’s main colour is blue, and the DPP’s is green.

Contrary to popular belief, the People’s Republic of China is not a one-party state. There are several political parties active in mainland China under the “umbrella” of the CCP. They are anything but independent. Interestingly, one of these permitted parties is the KMT itself, which maintains a limited presence on mainland China.

Edit: I originally called this a ‘Wade-Giles romanisation’, but Wade-Giles was specific to Mandarin. I’m not aware of there having been a formalised system for romanising Cantonese at the time that the ‘Chiang Kai-shek’ name became popular.

This meant that Taiwan previously had a veto over UN decisions, a power they used in 1955 to block Mongolia’s admission. Poor Mongolia.

I’ve found that having decent knowledge of the geography of a place you’re visiting enhances travel a lot, and makes it easier to chat with people. I recommend playing the geography quiz on Seterra to memorise all the Chinese provinces. I also made spaced repetition flashcards for the province and dynasty capitals.

I previously blogged about Sun Yat-sen in the context of him being a Georgist.

As a child growing up during the Irish financial crisis, I first learned about the Ming dynasty the same way everyone else did: as the nickname of Luke ‘Ming’ Flanagan, the independent Member of European Parliament whose beard makes him look like an ancient Chinese emperor. Believe it or not, I randomly bumped into Ming Flanagan while writing this section of the post. I found it too difficult to explain why I was writing a footnote about his beard.

Manchu, not Mandarin, was the official language of China until 1912, despite the fact that it has fewer than 20 speakers today.

A new spin on the thesis of oriental despotism?

Precursors to full Japanese control of Taiwan were raids on the indigenous population, most famously in the Mudan Incident. I don’t know how I missed it at the time, but the skulls of the victims of Japanese war crimes from this period were, for some reason, owned by my alma mater. The University of Edinburgh, quite literally, has skeletons in its closet.

Yet another example of the strong presence of numeric epithets in Chinese political culture.

I got that number from a book called Emergent Tokyo: Designing the Spontaneous City, which analyses the way that such an economic setup influences urban life in East Asia.

Most Chinese restaurants also don’t own ovens.

The owner of the venue in Taoyuan accidentally served me something containing peanuts (twice). She felt so bad that she gifted me a teapot with Taiwanese calligraphy, and introduced me to her son (?).

My favourite part is when one of the co-hosts offhandedly mentions Chang’s “unlikely” success dominating the global semiconductor industry from Taiwan and he retorts “Unlikely… in your opinion!”. Legend.

Although I recently learned of just how much regional heterogeneity there is in Chinese fertility.

With the partial exception of Nepal, although who knows what their Discord server will declare next.

This is fantastic Sam! You mentioned it would be a long piece but not that it would be so packed with data, no fat anywhere (rare these days). Thank you for the time you put into it.

Yea I think you’re too cool for schwarzman and you wouldn’t actually learn chinese it’s a post professional program 85% of the kids go into investment banking or consulting. Just spend a month or two in a language school see if you actually like it