My Speech to the Bertrand Russell Society

Henry George and the death of the land tax movement

I was recently invited to give a talk at the annual Bertrand Russell Conference, which is an academic gathering about all aspects of the life and thought of the philosopher Bertrand Russell. This year, it was hosted by Western Kentucky University, but that’s rather far away, so I gave the talk over Zoom. At first, I wanted to speak about Russell’s time lecturing at the University of Peking in the 1920s, and how he intersected with debates about Chinese language reform and the translation efforts of the New Culture Movement. But it turns out this topic has already been relatively well covered elsewhere. So, instead, I gave a presentation called “Henry George and the Role of a Land Tax in Bertrand Russell’s Political Thought”.

The subject matter sounds, and is, extremely niche. But if you think my interests are niche – and I say this with affection – you should have met the other guys.

This experience taught me the little-known geographical fact that Kentucky straddles two time zones. Fortunately, this resulted in me showing up an hour early rather than an hour late.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of what I said. You can also look at my slides here. My slides contain some bonus material I didn’t have time to get to about the French physiocrats and about why (and if) Karl Marx displaced Henry George as the dominant intellectual influence on the British left. Enjoy!

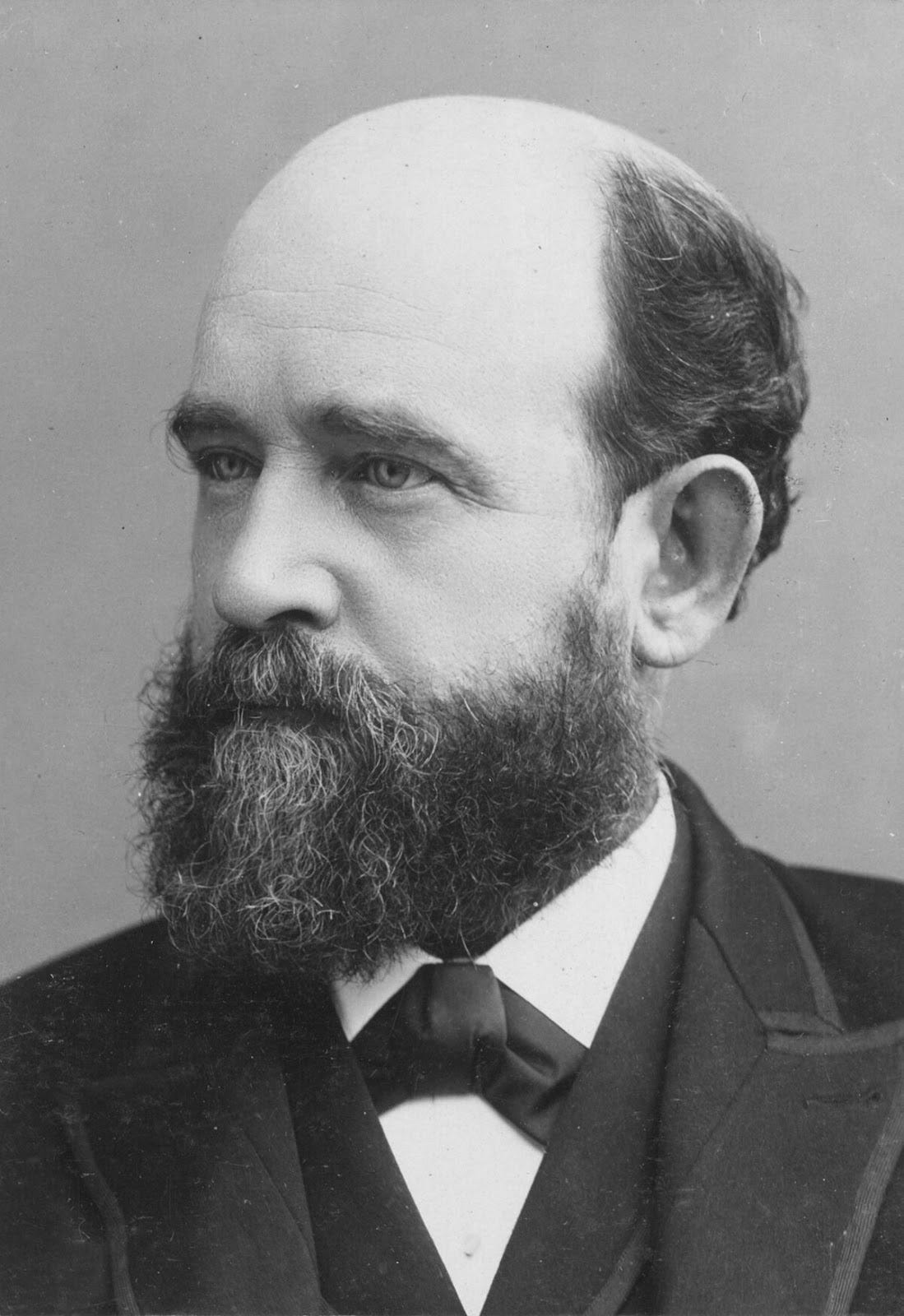

Hello everyone. Thank you very much for having me. Today, I’m going to be talking about this man here:

His name was Henry George. I’ll be talking about the ideas he had toward the end of the 19th century about land tax.

I hope to convince you that considerations about the taxation of land are actually quite important when considering anyone active in the worlds of social and political thought at the time that Bertrand Russell was.

The context of how I got interested in this rabbithole is this passage in the first volume of Russell’s Autobiography:

My Aunt Agatha introduced me to the books of Henry George, which she greatly admired. I became convinced that land nationalisation would secure all the benefits that Socialists hoped to obtain from Socialism, and continued to hold this view until the war of 1914–18.1

This quote raises a few questions: What was Henry George saying such that Russell interpreted him as advocating “land nationalisation”? And why did he abandon this view in the 1910s?

I’m going to split this talk into four parts. First, I’ll give an introduction: Who was Henry George? What kind of influence did his ideas have? Then, I’ll talk about the direct references that I was able to find, by Russell, to Henry George. Then, I’ll mention a little bit about the Land Question in various countries – roughly, who should own the land and why? Then I’ll conclude with a few comments about whether Russell would have more naturally had a political home remaining a Georgist.

Henry George

Henry George was an autodidact political economist, born in San Francisco in 1839. His really big idea that he became famous for is the concept of a land value tax. A land value tax is a tax on the unimproved value of land. Property taxes tax the value of any buildings or improvements you have on top of land, and the land itself. But land value taxes only apply to whatever the land would be worth if the plot were empty. If you convert this into an annual rate, it’s called the implicit or imputed rent of the land.2 George argues that the land tax should be set at 100% of the implicit rental rate.

So, if the rent for empty plots where I live were 7% of the total selling value of the plot, then all seven of that percent would go to the state. George further thinks that this should be the only tax; that all government activities should be funded through the land value tax. So this is, of course, quite a radical idea.

He first proposed it in an obscure pamphlet from 1871 called Our Land and Land Policy. But in 1879, he wrote a book called Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Causes of Industrial Depression and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth: The Remedy. I’ve always been impressed by just how 19th-century this book title is, and how it manages to have two colons in it.

This book was an extraordinary success. It became part of a kind of working-class political and economic canon. You will sometimes see it written that Progress and Poverty was actually the most widely read book in the entire English language in the 19th century, after the Bible. We can get into this in the Q&A, but the bibliographic data from the 19th century is so terrible that I don’t really trust this claim.3 But it certainly sold millions of copies and was incredibly influential.

What George was aiming to explain with his advocacy of this Single Tax was: How is it possible that we have things like industrial depressions? How is it possible that we have both progress and poverty? (The book is undeniably descriptively titled.) How do we have more homeless people, and destitute poverty in the centres of cities, when there are such large and totally undeniable improvements in industrial technology?

George’s answer is that the value of these improvements gets captured by increases in rent. And so the only solution is to ensure that it’s no longer profitable to hold on to land without improving it.

I believe this photo is from Ohio in 1914, where somebody bought an empty plot of land just to sit on it and wait for the value of land to increase. And he did this specifically so that he could buy a billboard to promote the ideas of Henry George.

One question that you might have about all of this is whether George’s idea of a 100% land value tax, is that the same thing as land nationalisation? Russell seems to think so. This has been an enduring point of discussion for Georgists. If you have a tax of this kind, is this basically the same thing as the government owning all of the land, and merely deciding to rent it out to people? Personally, I still can’t tell whether this is an interesting question for political philosophy, or just a semantic quibble.

In volume two of the Autobiography, Russell writes about how Georgism was previously considered an “active competitor” to socialism, especially in his undergraduate days, especially at Cambridge. He calls George a “forgotten prophet”.

To give a sense of just how much his extraordinary level of cultural influence faded, there’s this poll, which can be found in the book The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, that found that among early Labour MPs, Henry George was literally more popular than Shakespeare.4 Similarly, when Henry George died in 1897, over 200,000 people came to his funeral in New York, which was about 10% of the entire population of the city at the time.5

Another tidbit that you will come across if you ever go down this rabbit hole is that the board game Monopoly was actually created to promote the ideas of Henry George. Monopoly was based on an earlier game called The Landlord’s Game. There’s a fascinating and surprisingly complicated history there, but basically, the original elements of the game that promoted Georgism were removed, and the intended message was reversed.

Finally, I want to say a little bit about how Henry George has been treated in modern economics. An economist would say that the thing that’s special about land, that makes it fundamentally different from capital, is that land is perfectly supply inelastic. We can’t make any more land. There’s a fixed quantity of it; the supply curve of land is vertical.

George says that, even things like dredging land from the sea, like they’ve done in the Netherlands, is just transforming preexisting land. He says that’s not even a legitimate example of creating new land.

My sense is that modern economics has been surprisingly supportive of Henry George. Milton Friedman famously described land tax as the “least bad” tax. Joseph Stiglitz wrote an influential general equilibrium model in 1977 in which he showed that, under certain assumptions, the increase in aggregate rent will be at least as much as the cost of beneficial public investments. This is called the Henry George Theorem, and you can think of it as a kind of formalised version of the Georgist idea that improvements in amenities get eaten up by the rent increase.

Bertrand Russell on Henry George

Next, I’m going to talk about Bertrand Russell’s direct commentary on Henry George. So, Russell has this book from 1916 called The Principles of Social Reconstruction. It’s known as Why Men Fight in America. He says in this book that private property has no justification.

It’s sort of a historical accident that people have the property that they do. In his discussion of this, Russell is at his most explicitly Georgist. For example, he says that even though private property is unjustifiable, we should not abolish rent entirely. A system in which the government taxes people in accordance with how high their ‘free market’ rent would be, and then redistributes that money, has the benefit of penalising inefficient uses of land. If we abolish rent entirely, it will create a kind of lazy and conservative aristocracy out of the lucky few whose rent was high before the abolition. So in this, and in a couple of other ways, he’s basically hitting all of George’s talking points, in terms of having a land tax.

Jumping forward a bit, the next reference that I was able to find to Henry George directly in the works of Russell comes from this letter that he wrote to Constance Malleson in 1918, who was Russell’s love interest at the time. This one’s pretty hard to get a hold of, but I managed to find a copy in volume 14 of The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell.

This is a short letter, but he makes a couple of interesting points in it. One is that he discusses Georgism as basically being a continuation of the classical tradition of political economy, particularly John Stewart Mill’s Principles of Political Economy, and also, David Ricardo.

Ricardo has this idea called the Law of Rent. We don’t have time to fully get into it, but it’s viewed as a conceptual cornerstone of Georgism. Another thing I found that was very funny about this letter is that, possibly because he’s trying to impress a girl, Russell makes the very implausible claim that his friend Crompton Llewelyn Davies6 – who features quite notably in the first volume of the Autobiography – is the main reason why a Georgist-style land tax was featured in David Lloyd George’s budget from 1909.

Most of you are American, so maybe you don’t know this. But the 1909 budget is perhaps the most famous budget in British history. It’s known as the People’s Budget, and it caused a constitutional crisis that eventually led to the House of Lords losing its ability to veto legislation. One of the really interesting provisions was that it featured a land tax, but the land tax was on increases in implicit rent, rather than the level of implicit rent.

So if the unimproved value of land in a certain area had stayed exactly the same from a baseline level from 1909, then there would be no land tax. I haven’t been able to track down the full details of this, but Winston Churchill, who was then President of the Board of Trade and helped Lloyd George, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, draft the budget – Churchill said on many occasions that Henry George was irrefutable. So, presumably, they would have preferred a full land tax, but they viewed this one as more politically feasible. In chapter seven of the first volume of the Autobiography, Russell explicitly talks about the People’s Budget as a primary reason why he wanted to enter politics after the completion of the first volume of his masterpiece Principia Mathematica.

Here is a political caricature of an infamous self-assessment form called Form 4 and the logistical complexities that were involved in implementing the land tax.

The next reference, as far as I can tell, is in The Prospects of Industrial Civilisation from 1923. This is one that Russell co-authored, or is claimed to have co-authored with his second wife, Dora Black.7

Russell is moving away from George in this book. He seems to think that Georgism was kind of the logical next step in the development of liberalism. He believes that all of these terrible things flowed out of this historical accident of private property. But, communism clearly involves such a high level of coercion and despotism, such that, George is a kind of middle way between these. [Edit: Relevant context is that, in 1920, Russell published a book called The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism, which was based on a trip he had made to Russia (during which he met Vladimir Lenin!). In that book, he disavows the Soviet Union, which alienated him from many of his friends like Sidney and Beatrice Webb.]

In Prospects, he’s talking more about Henry George as a historical development of a set of ideas, rather than it being something that he subscribes to himself. And I think that he’s more realistic about the kind of contradictions with this view. For example, he openly speculates about whether it’s actually possible to implement a Georgist land tax, without an unacceptable level of state coercion.

The next reference to George by Russell is quite a bit later. It’s in a book called Freedom and Organization, published in 1934. I think this one is called Freedom versus Organization to Americans, although even the British title has the American spelling of the word ‘organization’, which I’ve always thought was odd. [Edit: This comment garnered a few chuckles, because the first talk of the morning was about the differences between the British and American versions of one of Russell’s books.]

You might notice that the Georgist perspective on land has a very clear parallel with the idea of surplus value, from Marx. This talk is not about Marx. I know almost nothing about Karl Marx. But I understand the “surplus value” to mean something like, the difference in the actual price of things and the “socially necessary” amount of labour required to produce it.

And although Russell was of course not a Marxist, he views the concept of surplus value as more salvageable than other elements of Marxism. In Freedom, he explicitly contrasts the way Marx and George analyse certain problems, and says George is much closer to being correct regarding the “analysis of power of money”.8

So again we see Russell is moving away from Georgism. He sees it as something that has an element of truth, but isn’t really applicable to modern problems. There’s a recent book from Christopher England, which is the first proper intellectual history of the influence that Henry George had on New Deal liberalism in the United States, and on the Liberal Party – for example, in the drafting of the People’s Budget. That book has a section about Russell, which is a little bit simplistic. What he says is that even after he moved away from being a Single Taxer directly, Russell always had a soft spot for George because of how incredibly straightforward George is. Progress and Poverty, to be honest, is actually quite an unpleasant book to read, because he just hits you over the head with the same idea over and over again.

You can’t accuse George of being vague. He’s using terms like ‘rent’ and ‘capital’ and ‘land’ in extremely specific ways. For example, by ‘wages’ he actually refers to a proportion, not an absolute quantity.9 And as he’s using the terms, land is not wealth, and neither is money.

And Russell contrasts that with Marx, who he criticises for never consistently using terms like ‘rent’. Another important book, Alan Ryan’s study from 1981 about the political life of Bertrand Russell, says that essentially, Russell thinks that everything that’s salvageable in Marxist ideas of surplus value and exploitation is more articulately and rigorously stated in the Henry George critique of monopoly. We've been discussing his critique of monopoly in the context of landowners having a monopoly over land, but George certainly also wrote many things about antitrust and monopoly in a corporate context.10

Weirdly enough, the main way that you get a sense that Russell moved away from Georgism is that he mocks other people for holding the view. For example, he stayed at one point in Massachusetts in the home of a very eccentric tennis player called Fiske Warren. They never actually ended up meeting in person, but in the Autobiography, Russell calls him a “fanatic” on the Single Tax issue.11

Fiske Warren had established a colony in Andorra, as part of a hare-brained scheme to disprove the Malthusian theory of population by having Americans buy up a large fraction of the country and create a Georgist microstate. Russell similarly mocks Crompton Davies as being a “fanatical” Gorgist, and writes about it as if it were one of the enduring eccentricities of their friendship.

In the first volume of his Russell biography, Ray Monk takes umbrage at this latter description. He says that Russell, at the time that he was mocking Crompton Davies for being a Georgist, also says elsewhere in the book that he believed exactly the same thing at the same time, for the same reasons.12 So it’s quite unclear if this is just Russell being very, very sloppy in the way he describes his own beliefs, or what exactly is going on there.

The Land Question

Henry George is quite explicit that he thinks that one of the effects of a land tax is that it will cause people to leave the cities and basically go back to farmland. And he has a very different view on why cities exist in the first place compared to modern economists. He makes no mention of network effects or knowledge spillovers, which are two of the main concepts modern economists apply to thinking about cities.

George thinks that people are kind of coerced into the cities, through being unable to afford the rent due to land speculation. This is also what he thinks is the cause of “industrial depressions”.13 This is incredibly ironic, because I sometimes talk about Henry George with people in Silicon Valley, for example, where there’s been a major recent resurgence in his ideas. And they are often under the impression that Henry George is the godfather of high-density walkable urbanism, or something like this. But actually, he thinks that the effect of a land tax will be to move toward a more rural society, rather than to intensify land use!14

I bring this up because, in Russell’s writings about China from the 1920s, he does seem to have a lot of this anti-city, anti-industrialisation kind of scepticism. He definitely had a “victims of our own success” perspective on all of the effects that industrialisation has had on the West.

Russell worried a lot about whether China would be able to catch up on Western science without also adopting its values. From what I’ve read of Russell, this is really him at his most Malthusian. He says repeatedly that poverty and famine will be endemic in China unless they have a widespread adoption of birth control or other population control measures.

This is kind of interesting, because one of the primary motivations for Georgism is precisely to have an intellectually coherent way to refute Malthusianism. Book II of Progress and Poverty is all about refuting the work of Thomas Robert Malthus. Around 1922, it seems a bit like Russell is subscribing to both schools of thought.

There’s a much more direct Georgist connection with China. After he played a key role in overthrowing the Qing dynasty, the economic pillar of Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People was based on the economics of Henry George.15 After everything fell apart and China descended into the Warlord Era, Russell wrote articles and also in his book from 1922, The Problem of China, strongly in favour of Sun’s government based in Guangzhou. This was against national stereotypes: most Brits at that time were inclined to support Wu Peifu’s faction in the north. He shared his sympathy for Sun with another world-famous philosopher who lived in China at the time, John Dewey.16 Russell was even invited to dinner with Sun Yat-sen, which to his “lasting regret” he had to turn down. But I wasn’t able to find any evidence that this enthusiasm for Sun was related to his adoption of Georgism.

I think Georgist themes similarly shine through in Russell’s interest in Ireland. I’m actually from Dublin, which is a fact which might be almost undetectable in my accent by this point [pause for laughter]. Henry George had an enduring interest in Ireland, particularly in how Ireland could be something of a test bed for his ideas. He wrote a book about the Irish Land Question, and he was arrested when he came to Ireland in the 1880s, while reporting on a series of protests against landlords for The Irish World.

Russell wrote and spoke about the Irish ‘Land War’ on a couple of occasions. He mentions in his Autobiography, very proudly, once shaking hands with Charles Stewart Parnell, who was the president of the Irish National Land League. The Land League was greatly influenced by George and his outlook toward questions of Irish land use.

In the first volume of the Autobiography, Russell also writes about his friendship with Michael Davitt, who was the founding organiser of the Land League, and recruited Parnell to it. He recalls going on walks with Davitt when he visited Ireland, and talking about the ideas of Henry George. [Edit: Something that casts a shadow over Bertrand Russell’s interest in Ireland is that his grandfather, John Russell, was prime minister for most of the Irish potato famine.]

Should Russell Have Been a Georgist?

I still don’t feel that we have a clear answer for why it was that Russell turned away from Georgism. He’s not at all explicit about his motivations for why he no longer subscribed to the Single Tax idea after around 1916. There’s this famous quote from Russell about how his life before and after the outbreak of World War I was as different as “Faust’s life before and after he met Mephistopheles”.

But I guess there’s still different elements to tease out about how it changed in different ways. Something that I think is rarely remarked upon is that George is coming from such a different intellectual tradition from Russell. For one thing, Georgism is explicitly religiously motivated! I’m never quite sure how literal he’s being, but in Progress and Poverty, he thinks that people moving away from cities because of the land tax will bring them closer to God. George was raised Episcopalian, and he is coming from a kind of 19th-century American Protestant social tradition, which is very alien – well, it’s alien to me – but it was certainly alien to an atheist British analytic philosopher.

That’s everything I have for now. Thank you very much!

Page 41 in The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, Unwin Paperbacks (1978).

I realise this might come across as a bit confusing, but I was speaking to a reasonably economically literate audience. It’s completely standard for economists to convert one-off costs into per-period rates. Here is my conversation with o3 explaining how this relates to amortisation and the discount rate.

See Lars Doucet, Land is a Big Deal, xvii for more discussion.

See table 1.1 of the book, which is in location 1363 in the Kindle edition. The author, Jonathan Rose, cites as his source ‘The Labour Party and the Books that Helped to Make it’, Review of Reviews 33 (106); 573–74. It doesn’t appear to be digitised, and I can’t find it in any library.

The table reports the result of a poll conducted after the 1906 General Election, which asked Labour MPs about their favourite authors, to which 12 responded ‘Henry George’ and 9 responded ‘William Shakespeare’. However, if you add up all the numbers in the table, you get 45. This is confusing, because there were only 29 Labour MPs total in 1906.

Now, you might think, the table could be reporting a poll conducted on anyone who had ever been a Labour MP. But I think the number of distinct individuals who had ever been a Labour MP by 1906 was still only 29. You can read my o3 conversation about this. I’m inclined to think that Rose has misunderstood this data, and that the poll allowed for the respondents to select multiple options (on the previous page, Rose implicitly denies this possibility by saying that 45 separate individuals responded). This is common between all three editions.

I emailed the author about this, asking for clarification, and I thank him for responding so quickly. What he now thinks is going on is that the Review of Reviews poll only allowed for one response per respondent, but the respondents also included “Lib-Lab” MPs, namely Liberal MPs who were financially maintained by trade unions. The Wikipedia list seems to suggest there were just about enough Lib-Labs in 1906 for them to sum to 45 when added to the number of Labour MPs. But several of these cases are quite ambiguous (e.g. people who switched parties almost immediately after the election).

All of this is a long-winded way of saying: I’m not sure exactly what is being claimed here, and I’m not sure there is a way to find out without getting physical access to a specific journal from 1906. If anyone can help me with that, please email me.

Lars Doucet, Land is a Big Deal, page 4.

I forgot to mention this is in the talk, but Crompton’s wife was the Irish Republican activist Moya Llewyln Davies, which was another of Bertrand Russell’s ties with Irish nationalists. Crompton’s nephews also inspired the creation of Peter Pan, which is an insane crossover.

I realise this comment might come across as condescending, but significant parts of the book had already been published before Russell even met Dora, so there has been some speculation over whether “Bertie” was being generous with his authorship credit to the point of dishonesty. See Ray Monk, Bertrand Russell: The Ghost of Madness 1922–1970, page 22.

I found out about this via The Basic Writings of Bertrand Russell, Routledge 2009 printing, page 495.

See page 137 in my edition of Progress and Poverty.

In the Q&A, we discussed Russell’s views on competition more generally, and one philosopher pointed me to Russell’s essay Why I Am a Guildsman. I remain confused about why Russell was getting more sceptical of free market competition in general, at the same time as he was becoming less enthusiastic about Georgism, which seems like a special case of insulating a specific industry from competition.

A friend said that this reminded him of the MMA fighter who recently said after a fight that his fans should read Ludwig von Mises and the six lessons of the Austrian School. Bring back athletes with strong opinions about political economy!

Ray Monk, Bertrand Russell: The Spirit of Solitude 1872–1921, page 43. The Monk biographies are controversial; contrast with this more sympathetic account from Peter Stone. Peter alerted me to this quote from Wittgenstein that Russell’s books should be bounded and divided into volumes with two colours: “those dealing with mathematical logic in red—and all students of philosophy should read them; those dealing with ethics and politics in blue—and no one should be allowed to read them”. Monk’s book about Wittgenstein was much more warmly received, and I look forward to reading it.

This is stated most forcefully on page 166 of my edition: “That land speculation is the true cause of industrial depression is, in the United States, clearly evident”.

Of course, modern Georgists can (and do) think that George is empirically mistaken about this prediction. While I’m not sure I entirely subscribe to Sam Watling’s interpretation, it seems that George’s clearest statement of the view that cities do not cause prosperity is in book V of Progress and Poverty: “It is not the growth of the city that develops the country, but the development of the country that makes the city grow” (page 169 in my edition).

There are some people who think that the influence of George on the early Republic of China goes deeper than that. In the Q&A, we had some speculative discussion about whether the lack of a history of strong organised religion in China was related to whether they would adopt the ideas of a “secular saint” figure like George.

Dewey was another prominent supporter of the land tax, and wrote about it more often than Russell did. He once wrote that “No man, no graduate of a higher educational institution, has a right to regard himself as an educated man in social thought unless he has some first-hand acquaintance with the theoretical contribution of this great American thinker [Henry George]”.