‘Protestant Magic’ Today

Nationalism and occultism in Ireland

The writer Manchán Magan died in October, less than a year after his astonishingly successful Thirty-Two Words for Field was republished with a new foreword. In that foreword, Magan summed up his worldview with great succinctness. The Irish language, he claimed, reflects ‘the accumulated knowledge of a people’:

an innately indigenous understanding that prioritises nature and the land above all things … [with] magic that our ancestors perceived in the natural world and the otherworldly realms that surround it.

In line with this view of the land and the magic embedded in it, last month (at an unconventional memorial service) Magan’s ashes were scattered at the Hill of Uisneach, the supposed ‘sacred centre of Ireland’.

The immense popularity of Magan’s books is in line with the widespread presence of this set of ideas in Irish culture. We are all so used to it, even if we don’t know what it is. This vision is of Ireland as fallen from ancient wisdom that we might return to; the idea of an inherently Celtic spirituality, or a deep connection to the land that is embedded in our language (and particularly the Irish language) and our way of life.

Yet these ideas don’t come directly from explorations in our ancient mythology or Old Irish literature, nor ‘deep’ traditions from our Celtic ancestors. Surprising as it might be, these ideas were generated in the nineteenth century, arising from the status anxieties of Irish Protestants in the face of Home Rule. This strange marriage of occultism and national identity has become a powerful but all-too-often missed aspect of Irish culture.

The logic of Protestant magic

In a 1989 lecture, the historian Roy Foster1 made a major contribution to understanding Irish cultural history when he came up with the concept of ‘Protestant magic’. He described a set of:

Marginalised Irish Protestants … [often] stemming from families with a strong clerical and professional colouration, whose occult preoccupations surely mirror a sense of displacement, a loss of social and psychological integration, and an escapism motivated by the threat of a take-over by the Catholic middle classes…

The Protestant minority in Ireland, making up around 20% of the island’s population in the Victorian era,2 had historically been the elite ‘Ascendancy’ class in Ireland. But from the late nineteenth century, the power of the Protestant Ascendancy declined and Catholics gained political and economic status. With Home Rule looming on the horizon, many Protestants felt increasingly ill at ease with their place in Irish society. What Foster observed was that this feeling was increasingly given outlet in esoteric, occult, and supernatural ways. Foster mostly focused on the literary products of this way of thinking, including Gothic supernatural novels like Dracula and Uncle Silas. But Protestant magic wasn’t just a metaphor: in the face of the Victorian-era decline in Christian belief, occultism became a real phenomenon among Irish Protestants, rooted in class anxieties and sectarian division but leading to real practice and real belief.

Ireland was not completely isolated here. Occultism took off in nineteenth-century Britain, especially at the end of the century, and the roots of modern neopagan religions like Wicca and Druidry can be traced back to this. But Ireland didn’t follow exactly the same trends as England. Irish Protestants shaped magic and the occult in their own ways, ways that were specifically Irish and – upon close inspection – specifically Protestant. The clearest example (and Foster’s own focus) was William Butler Yeats.

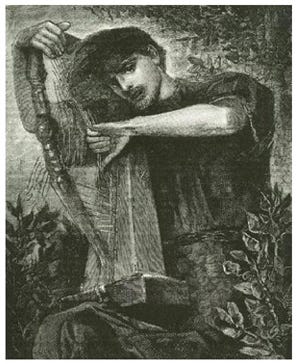

As well as a poet, Yeats was a regular practitioner of ritual magic, a dabbler in (sometimes drug-induced) mystic experience, and a student of esoteric literature. He was for a time a senior member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the most important of the many societies that branched off from Freemasonry in the nineteenth century and expanded its basic concepts into elaborate rituals, garb, and ‘high’ magic. And for a time, he devoted himself to creating a specifically Irish order of ‘Celtic Mysteries’ inspired by the Golden Dawn. Later in life, he would spend untold hours ‘channeling the spirits’ with his wife George, and credited these spirits with many of his richest metaphors and ideas.

None of this existed separately from his better-known role as a poet of Ireland and Irish nationalism; Yeats thought these two facets of his life were deeply interconnected.3 His 1892 poem ‘To Ireland in the Coming Times’ is essentially a manifesto for Protestant magic. Yeats declares that his standing as a national poet isn’t undermined by his concern with the occult and esoteric:

Nor may I less be counted one

Because, to him who ponders well,

My rhymes more than their rhyming tell

Of things discovered in the deep,

Where only body’s laid asleep.

Certainly, there were indeed people who doubted that Yeats was ‘authentically’ Irish. But these doubts (and Yeats’ own related anxieties) were because Yeats was a Protestant!4 Ritual magic didn’t have a whole lot to do with it.

Yet the way Yeats reacted to this suspicion was to swap Protestantism out for occultism. Now, rather than his Protestantism being ‘un-Irish’ when compared to Catholicism, he was suggesting that Catholic theology might actually be ‘un-Irish’ when compared to an ‘authentic’ occult Irish spirituality, which he described using Rosicrucian symbols. Ireland has been ‘a Druid land’ since time immemorial, or so Yeats claimed.

Yeats hoped for a future where ‘the thoughts of Ireland’ would brood once more upon the esoteric. But his hope for this future was rooted at least in part in the dynamic of being from a Protestant background, being anxious about status in Catholic and nationalist circles, and feeling the need to ‘authenticate’ his Irishness.

Those are the basic elements of Protestant magic. We have an interest in occult, mystical, or magical spirituality; an argument that this type of spirituality is authentically Irish; and, in the background, a status dispute over the place of Irish Protestants in the new, emerging social order of post-Famine Ireland. Foster pointed out, with a wide range of examples, that this was a general pattern among many Irish Protestants.

‘Ancient traditions’ and modern corruption

Many Protestant writers were inspired by the not-quite-a-historian Standish J. O’Grady, son of a County Cork minister. In 1878, O’Grady published a book that tried to reconstruct the supposed bardic tradition about Ireland’s pre-Christian ‘heroic age’, which he believed could be seen – albeit ‘overlain and concealed’ by later accretions – in medieval Irish literature.5 Unlike modern scholars,6 he was confident that he could figure out what was genuinely bardic and what was mere accretion, using the classic methodology of vibes.

‘[I]n order to be faithful to the generic conception’ of Irish culture, O’Grady declared, ‘one must disregard often the literal statement’. He defended himself by saying that bardic traditions are all about vibes:

[L]egends represent the imagination of the country; they are that kind of history which a nation desires to possess. They betray the . . . ideals of the people, and, in this respect, have a value far beyond the tale of actual events.

Importantly, talking about ‘the imagination of the country’ did not necessarily require hewing closely to what the country’s (majority Catholic) inhabitants actually thought. Language revivalist (and future President) Douglas Hyde, also a minister’s son, had warned in 1892 that Ireland had ‘ceas[ed] to be Irish’, and the body of the people had to be treated like ‘a corpse on the dissecting table’ until the Celtic spirit returned. Outsider revivalists like Hyde might actually be in a better position than Catholic peasants to pick out the traditions that were ‘most smacking of the soil’.

You’d be right to worry that, given this much freedom, folklorists and revivalists could discard anything inconvenient in old traditions and literature as ‘corruption’, and ‘find’ whatever they wanted to find.7 In turn, many Protestant folklorists subconsciously wanted to find evidence of native occultism, which could break the link between Catholicism and Irishness, and might justify their place in Irish culture. And so this is exactly what many of them ‘found’: remnants of a deeper ‘pagan’ spirituality, often concerned with fairies and supposedly founded in a profound Celtic connection to the land, that had been buried beneath peasant ‘ignorance’ and Catholic dogma. Yeats insisted that, while everybody had the potential for spiritual visions ‘if you scratch him deep enough’, fairy lore demonstrated that ‘the Celt is a visionary without scratching’.8

This is not to say that there weren’t uniquely Irish spiritual or fairy traditions. It’s just to say that Protestant folklorists weren’t uncovering these traditions so much as they were creating new ones.

Possibly the most famous expression of belief in occult Irish spirituality came in a letter to Yeats from the mystic and artist Æ in 1896:

The gods have returned to Erin and have centred themselves in the sacred mountains and blow the fires through the country. They have been seen by several in vision, they will awaken the magical instinct everywhere, and the universal heart of the people will turn to the old druidic beliefs. I note through the country the increased faith in faery things. The bells are heard from the mounds and sounding in the hollows of the mountains . . . Out of Ireland will arise a light to transform many ages and peoples.

Æ was born George Russell to a northern Protestant family, but became a Theosophist with a deep interest in mysticism and Eastern religion. Russell was not some weird figure treated with suspicion; he was right at the heart of Dublin’s literary and cultural scene for decades. He came to believe that his role was to fan the flames of mystic religion, both in his art and in his practical activities.

In 1897, still filled with manic energy and frustrated at those who opposed his mystical ‘revival’, Æ wrote to Yeats: ‘I came home last night big with radiant ideas and full of wrath over the priests’; it is notable that he himself made the connection. Foster’s lecture described how many Irish Protestants in the late nineteenth century felt ‘caught between the threatening superstructure of Catholicism, and recourse to more demonic forces still, against a wild landscape which they have never fully possessed’.9 And as the era came to a close, many chose to see that which orthodox Protestantism viewed as ‘threatening’ and ‘demonic’ as actually offering spiritual insight that should be embraced.

The spread of Protestant magic

Whatever the origins of Protestant magic, it didn’t stay within the Protestant minority for long. Even if people weren’t going looking for the occult and the magical, these ideas permeated much of the literary culture of Ireland during the Gaelic Revival. And so, as Revival ideas of Irishness spread, so too did Protestant magic, a subterranean current.

Of course, for those who discovered a taste for it, there was an explicitly occult or mystical tradition in Ireland, kept alive into the twentieth century by works like James Cousins’ 1912 The Wisdom of the West, which (roughly) argued that Irish fairies are avatars of Hindu deities.10 But increasingly, works that emphasised the occult and religious nature of these ideas were less important to their spread. Thanks to its presence in the works of great creative writers, Protestant magic had a certain slipperiness, and could metamorphose from literal belief to literary metaphor and everything in between. This was what allowed it to diffuse throughout Ireland, as a set of ideas that were often simply stored in a different part of the mind from religious dogma. This was especially important as the number of Protestants in the newly independent Irish Free State sharply declined; going forward, Protestant magic would be disconnected from its origins.

Another feature of Irish culture contributed to this. As the historian Richard Bourke has put it, in Ireland ‘there’s been a relative dearth of what you might call dedicated intellectuals and, by comparison, a dominant role played by the image of the writer, in a more traditional literary sense.’ In Irish culture, the lines between different writerly vocations are blurred, much more than in England or America: novelists write historical essays, journalists write literary memoirs, historians analyse poetry, literary critics survey political discourse.

On the one hand, this has aided interdisciplinary creativity, and led to some works of genuine brilliance. But on the other hand, it means that we tend to conflate different standards of judgment, and rank books based on the wrong thing: whether that means judging literature or history according to the standards of contemporary politics, or else judging theology or philosophy solely on its creativity and literary merits, ignoring whether it is true or well-argued. This has created conditions perfectly suited for Protestant magic to thrive. Because it has the weight of the Revival behind it, it has been able to embed itself in our culture without very many people ever looking at it straight-on, and shaped the way we think about key issues. I will look at three examples: the environment; religion; and the Irish language.

Protestant magic and the environment

The Kerry mystic John Moriarty was a great example of Bourke’s description of the ‘writer’. After a relatively unsuccessful period in the 1960s and 70s as an academic, Moriarty was ‘discovered’ by the RTÉ broadcaster Andy O’Mahony in the mid-1980s, and published a dozen volumes in a great burst of activity between 1994 and his death in 2007. His first 1994 book, Dreamtime, was launched at the Clifden Arts Festival by future President Michael D. Higgins; in 1997, he was given his own RTÉ miniseries.

Moriarty relied heavily on self-presentation and tone. In books and lectures, he would deploy a rapid sequence of unexplained references to religious and philosophical texts, to give the impression of deep esoteric knowledge and quickly unfolding ideas running one into the next. But lifted out of the network of esoteric references, many of his reflections come to seem trivial or even comical: ‘In the last century . . . somehow, women have enfranchised themselves . . . I just want to say, why don’t we also go further and enfranchise the universe?’11

As this line might suggest, Moriarty’s particular preoccupations were very ecological and environmental. He presented readers a stark choice: ‘shape Nature to suit us,’ or ‘let Nature shape us to suit it’; and he comments that ‘everywhere there is evidence that we have chosen wrongly’.12 He blamed this on the Western ‘modern mentality’, but hoped that opening ‘the old pagan window’ and connecting with Ireland’s landscape and spirituality could overcome it.13

But when you look more closely at what Moriarty actually wrote about spirituality, there’s very little in there that’s all that Irish. As well as ecology and environmentalism, he drew heavily on Eastern religion, hoping that ‘bring[ing] together the two extremities of the Indo-European expansion’ could jolt Ireland out of Western modernity.14 He also developed his own idiosyncratic interpretations of Christian dogma, especially the ‘Triduum’ of Christ’s death and resurrection. And he owed maybe his deepest debt to the philosopher Martin Heidegger. Heidegger posited that the influence of science and rationalism disrupted the fundamental unity between human beings and the natural world, and called for an alternative form of consciousness, of ‘being in the world’. Moriarty’s references to Celtic myth provide colour, but the substance of his ideas come from elsewhere.

This contributes much to his sage-like slipperiness, where you have to chase down references to medieval Irish literature to understand any given paragraph – only to find that the references are pure window-dressing, and don’t matter for his argument. And, ironically, the fact that his Celticness is so surface-level is perhaps the most authentically Irish part of Moriarty’s work, because it shows him drawing on an entirely home-grown tradition: Protestant magic. Just like Yeats and Æ, Moriarty insisted that truly Irish spirituality is to be found in the esoteric and the mystical – Eastern religion, German philosophy, and a spiritual approach to the environment. And if you might worry that this doesn’t seem particularly Irish, Moriarty’s response is lifted straight from Protestant magicians of old: the actually-existing culture of Ireland is ‘in deepest gloom’, and the ‘[s]igns are that it has died’, because it’s lost its ecological unity. Only a ‘healer’ like Moriarty can identify that which is really Irish.15

The Celtic window-dressing was a huge part of what made Moriarty popular: by making an ecological sensibility seem both deeply spiritual and authentically Irish, Moriarty helped legitimate Irish environmentalism, just as that movement was growing in the late 1980s and 1990s. Among his best-known champions, alongside people like poet Paul Durcan and nature writer Tim Robinson, are popular figures like Tommy Tiernan; and through such champions Moriarty had a major, if oft-overlooked, impact on Irish writing and culture.

Protestant magic and religion

As might be suggested by the above mention of the Christian Triduum, Moriarty was also an exemplar of a second important trend: the reinjection of Protestant magic back into Christianity, in particular Catholicism. Decades after Yeats’ death, by which point the Gaelic Revival had become a key part of Ireland’s cultural inheritance, interpretations of Celtic spirituality that were rooted in a Protestant context and occult interests actually began to shape the practice and self-understanding of religious Catholics.

Back in the late nineteenth century, devout Catholics had been radically opposed to the ideas we’ve been discussing.16 This opposition only increased after independence, when the now world-famous Yeats began to position himself very explicitly as a defender of Protestant aristocracy and Protestant interests in the new Free State, with Catholic writers and newspapers linking the occult symbols in his poetry to Ascendancy culture.17

But by the midcentury, Christianity (both Protestant and Catholic) found itself pulled by all sorts of reformist tendencies, of which the ‘spirit of Vatican II’ was only the most famous. Many felt the need for new ways of expressing Christian spirituality, including a newfound interest in ‘Celtic Christianity’: the alleged traditions of Christianity in Britain and Ireland as they had existed before change was imposed from Rome.

The idea of Celtic Christianity had historically been a Protestant notion: the early modern Presbyterian thinker George Buchanan argued that the Reformation, rather than introducing anything new to Britain and Ireland, had merely been a return to a native Celtic Christianity that rejected Rome. But in the twentieth century, the reach of the idea expanded, especially after the 1960s republication of the Carmina Gadelica, a famous Victorian collection of prayers and hymns translated from Scottish Gaelic to English. In the following decades, many books were published in both Britain and Ireland, helping shape ‘Celtic Christianity’ at the same time that it was increasingly being practised in new Christian ‘communities’ and on religious retreats.

There is nothing wrong with an interest in medieval religion, of course. The problem was that most people who were interested in Celtic Christianity, both in Britain and in Ireland, were monolingual English speakers, and translations of key texts were rare and often out of date. There were certainly careful scholars who could read and write Old Welsh or Old Irish, and who did detect a distinctive religiosity in these texts, often focused on the Trinity. But such efforts were vastly outnumbered by books which relied on a small handful of English translations (like the Carmina or the ‘Breastplate of St Patrick’); all too often, the gaps where Old Irish scholarship should have gone were filled by modern assumptions and presuppositions.

And many – especially in Ireland – had assumptions about Celtic spirituality that were syncretic and occult. Inspiration was taken from Eastern religion; while few went as far as writer Shirley Toulson, who declared in The Celtic Alternative (1987) that Celtic Christianity ‘had more in common with Buddhism than with the institutional Christianity of the West’, nonetheless many communities inspired by Celtic spirituality began to incorporate a new type of focus on the self and new approaches to meditation into their religious practice. Relatedly, various spiritual practices inspired by the ‘New Age’ movement began to appear in Celtic Christianity, a phenomenon that was noted both by defenders and critics.

It might be assumed that the Catholic hierarchy would have resisted these trends. But the power of unspoken occult assumptions about ‘truly’ Irish spirituality, inherited from the Revival, meant that things ended up involving more negotiation. The writer John O’Donohue was the absolute exemplar of these trends. Ordained as a Catholic priest in 1982, O’Donohue’s developing theological ideas brought him into conflict with the hierarchy, and he stepped back from his duties in the 1990s. For O’Donohue, as with Yeats and Æ before him, the ‘Celtic tradition’ and folk Catholicism contained deep truths that orthodox Catholic theology ignored, especially around sex and the body.18 His bestselling 1997 book Anam Ċara used neopagan-esque language to try to reinvigorate Christianity, declaring that ‘Celtic spirituality hallows the moon and adores the life force of the sun’, and celebrating how ‘ancient Celtic gods were close to the sources of fertility and belonging’.19 Among its short chapters are stories about Zen monks, pieces of fairy lore, and at one point a chapter that is more than half taken up by a Yeats poem.

Yet, when O’Donohue died in 2008, four bishops and a ‘large number of priests’ from across Ireland attended the funeral. The fact was that in the intervening years, ‘Celtic spirituality’ and associated religious practices had become extremely popular among devout Catholics, especially via ‘retreats’ to religious centres or ecumenical communities. The ground had shifted within Irish Catholicism. It helped, too, that O’Donohue never felt the need to be clear about how far his use of neopagan and esoteric language was to be taken literally, and how much it was just literary ‘borrowing’. Celtic spirituality became popular, partly because it helped satisfy the desire for new forms of religious practice, but – equally importantly – also because it rhymed with the spiritual self-identity of many Irish people: a spiritual self-identity shaped by the influence of Revival occultism.

Protestant magic and language

As the previous section suggested, for many Irish people, the Irish language acts as a barrier to accessing their country’s religious and intellectual history. The resulting temptation is to see the language as a kind of ‘key’ to esoteric knowledge. When combined with Ireland’s wider conflicted stance towards the language,20 it’s not surprising that some people have come to believe that there is a kind of spirituality embedded into the Irish language itself: its vocabulary and grammar and structure, not just the stories and ideas expressed using it.

The idea is that Irish, especially in its vocabulary relating to the natural world and spirituality, can make distinctions and subtle observations that are awkward or impossible in English, which reflect a special Irish outlook on the world. The recently deceased Manchán Magan, who was something of a disciple of Moriarty’s, has been the greatest and most successful contemporary exponent of this argument, most famously in his 2020 book Thirty-two Words for Field which became an explosive bestseller. (As I write these words, Magan is still on the bestseller lists with his follow-up volumes.) But he was drawing on a much longer stream – a stream that, to some degree, goes all the way back to Douglas Hyde.21

Like many in this tradition, Magan himself knew the language quite well as a speaker, but his understanding of its history and deeper structure was weaker. The effect was compounded by writing in English for an anglophone audience: the job of rigorous fact-checking was left to anonymous bloggers – who duly found a whole host of errors after publication.

Magan’s understanding was at its weakest when comparing Irish with languages that he didn’t speak, especially Indian languages. But he made the effort of comparison anyway, because he wanted to prove that Ireland and India retained traces of an earlier Indo-European consciousness that had been gradually eroded away elsewhere. As Magan put it, he wanted to show that ‘Gaelic and Hindu culture are manifestations of the same spiritual and cultural past.’

In response to this, a different perspective on the Irish language might point out how unique and unlike other languages Irish is; how rapidly the language seems to have departed from its Celtic and Indo-European roots, experiencing rapid vowel shifts, a division between ‘broad’ and ‘slender’, and the introduction of a complicated and almost-wholly-unique system of mutations, all in a period of barely 200 years: the last Ogham inscriptions in ‘Primitive Irish’ have obvious similarities with other Celtic and Indo-European languages, but only a short while later, we have ‘Old Irish’ that looks radically different from anything else. This is objectively extremely interesting, and might make a good subject for a popular book.

But it doesn’t fit with the dubious notion that the language embodies deep wisdom, stretching back into the misty Celtic past: these changes to the Irish language happened centuries after the Celts settled Ireland, and maybe even after the arrival of Saint Patrick. That is to say, the language roughly as it now exists is barely older than the highly literate and literary culture of Christian monasticism. Certainly, there are still some elements of the Irish language that reflect older Indo-European roots – but then, exactly the same is true of English.

But Magan’s anglophone readers, in general, have been less concerned with the accuracy of this or that claim about vocabulary or history; in the tradition of O’Grady, what they instead are looking for is a vibe.

Magan’s popularity, and the fact that his way of thinking about the Irish language and its importance is so widespread, tells us little about the Irish language itself, but a great deal about the way Irish people think of themselves, their nation, and their spirituality.

Protestant magic today

When people write about the impact of the Gaelic Revival on Irish culture, the focus is often on its relationship with politics: whether that’s to do with the lead-up to 1916 and the war of independence, or with the legacy of Revival nationalism in Irish economic policy. In more recent times, more and more people have been looking to different sides of the Revival, and especially its religious and esoteric dimensions, many influenced by Roy Foster. But it’s still underappreciated how this aspect of the Revival has lingered into the present day, and still conditions the way that many Irish people think about their nation, and about such vital cultural topics as land, religion, and language.

There is, of course, nothing inherently wrong – and certainly nothing un-Irish – about this. Indeed, Protestant magic, the unification of occultism with national identity, is an entirely home-grown tradition which has given rise to some of Ireland’s greatest literary gifts. But it’s not home-grown in the sense of genuinely ancient or authentically ‘Celtic’; it’s Victorian, it’s deeply modern, and it’s the product of a class (Irish Protestants) whose place in the national story is very far from simple and often deliberately downplayed.

Occult, magical, mystical, or spiritual ideas, outside mainstream religion, are often neglected when we think about cultural and intellectual history. But in Ireland, the occult ideas of Victorian Protestants have deeply shaped many people’s identity and self-understanding. Understanding this is important to understand the culture of the country, and also perhaps to help jolt us out of complacency about that culture; their origins help us see just how strange many of our ‘natural’ assumptions about land and religion and language are.

Peter McLaughlin is associate editor of The Fitzwilliam and an Emergent Ventures winner. He writes the blog Her Fingers Bloomed. You can email him at peter [at] thefitzwilliam [dot] com.

When our non-Irish friends have heard of Roy Foster, it is often because of his superb appearance on the Conversations with Tyler podcast.

Although this was not evenly distributed across the whole country: the Protestant population in the area that is now the independent Republic of Ireland was closer to 10%.

Last year on my personal blog I wrote about nationalism in Yeats from a very different perspective: the extent to which he treats nationalism as a tragedy. Between Yeats’s mockery of the ‘Paudeen’ and the well-known issues that Jonathan Swift had with Catholics, perhaps it is worth penning something on Ireland’s habit of adopting national heroes who don’t like us very much.

For a good example of Yeats’ youthful anxiety that only Catholics could be ‘authentically’ Irish, which he would come to sublimate into occultism, see the description of his views on the Catholic-turned-Protestant writer William Carleton in R. F. Foster, W. B. Yeats: A Life, vol. 1, pp. 97–98.

O’Grady, in turn, was drawing on a wider cultural interest in ‘Celticism’ that had been growing across the UK since the publication of the infamous Ossian forgeries in the 1760s, helped along by the development of comparative linguistics and philology. For this wider cultural trend see Patrick Sims-Williams, ‘The Visionary Celt: The Construction of an Ethnic Preconception’, Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies 11 (1986) 71–96. Seamus Deane has argued, tantalisingly, that the way these influences got applied in the Irish context owed something to the great political theorist Edmund Burke: see ‘Arnold, Burke, and the Celts’ in Deane, Celtic Revivals.

The best modern work on the ‘mythological cycle’ of medieval Irish literature is the first half of Mark Williams’ Ireland’s Immortals: A History of the Gods of Irish Myth. We are still waiting on a work as good as it about the other ‘cycles’, which deal with such figures as Fionn mac Cumhaill and Cú Chulainn; but Williams’ other book, The Celtic Myths That Shape the Way We Think, is an ok introduction to some relevant topics, and includes recommended readings at the back.

For a critical evaluation of the methods and assumptions of many folklorists, see Gillian Bennett, ‘Geologists and Folklorists: Cultural Evolution and “The Science of Folklore”’. Ronald Hutton’s The Triumph of the Moon, ch. 7, highlights parallel processes in folklore-collecting in England.

Yeats, Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, p. x. Foster’s lecture on Protestant magic has a brilliant example of exactly how folklorists like Yeats distorted what they heard in order to fit what they wanted to believe: ‘It was necessary for Yeats passionately to adhere to the idea that Sligo people did believe in fairies and talked about them all the time. So they did, of course – to children’.

Foster, Yeats: A Life, vol. 1, p. 178.

This strand gained an international audience with The Fairy-faith in Celtic Countries by Walter Evans-Wentz, a Theosophist influenced by Yeats and Æ. He would become famous for bringing Tibetan Buddhist ideas to the West as the ‘discoverer’ of the so-called Tibetan Book of the Dead in 1927.

This clip is played in the first episode of the podcast series The Bog Shaman, but I can’t now find the original.

Moriarty, What the Curlew Said, p. 16.

Moriarty, Invoking Ireland. See also Moriarty, What the Curlew Said, p. 14, or Dreamtime, pp. 7–8, for key examples, though the idea is expressed repeatedly throughout all his books.

Moriarty, Dreamtime, p. ix.

Moriarty, Dreamtime, pp. vii–viii, 60.

A key example came in 1895, when a mentally ill farmer in County Tipperary burned his wife to death, claiming she was a fairy changeling. The story became an occasion for a full-pronged attack by orthodox Catholics on those who gave encouragement to such dangerous ideas as fairy-lore. A whole book has been written about this event and its place in Irish history: Angela Bourke, The Burning Of Bridget Cleary.

In particular, many Catholic commentators were much exercised in the 1920s by Yeats’ occult interest in the Greek myth of Leda: Zeus appeared to Leda in the form of a swan and raped her, making her pregnant with twins Clytemnestra (who would later kill her husband Agamemnon) and Helen of Troy; Yeats thought this embodied an occult truth about recurrent patterns in history. The Catholic Bulletin condemned Yeats’ symbolic use of the rape as violent and immoral, and linked this immorality to his Protestantism. See Foster, Yeats: A Life, vol. 2, especially pp. 268–274.

See especially O’Donohue, ‘The Body is the Angel of the Soul’, in Anam Ċara.

O’Donohue, ‘The Celtic Circle of Belonging’, in Anam Ċara.

A conflicted attitude that was perfectly diagnosed by the Northern literary critic Seamus Deane: ‘The loss of the Irish language was tragic and the attempt to revive it has been a farce.’

While not himself any sort of mystic or occultist, Hyde helped contribute to these trends, for example by helping out with Walter Evans-Wentz’s research into Irish ‘fairy faith’ and providing a (somewhat awkward) introduction.

Thanks for this Peter. I had never heard of Protestant magic before