Most Irish Foreign Aid Never Leaves the Country

But, weirdly, this is fine (for now)

Ireland is, by some measures, among the most generous nations in the world in its foreign aid. In 2023, the government spent over US$500 per capita on ‘development assistance’, the standard metric for foreign aid spending. That’s nearly twice the figure from the UK, which spent only about $250 per head of population that year. It’s also well above average per capita spending among the Development Assistance Committee (the group of countries that are considered ‘major donors’ in foreign aid), which in 2023 was less than $200.1

Sure, aren’t the Irish great? That’s us: big-hearted, generous people. A nation of philanthropists. The government certainly thinks so: in September 2025, the Tánaiste described Ireland’s foreign aid spending as ‘the embodiment of who we are and how we view the world’, and ‘a source of enormous pride’. The uniquely charitable ethos of the Irish people is chalked up to our experience of famine and British rule, and our history of generosity to those who need it.

It’s difficult to square these accounts with the fact that, in 2023, 55% of Irish development assistance never left the country, and was spent by the government on services at home. Genuine foreign aid makes up only a minority of Ireland’s reported ‘foreign aid’ spending.

This bizarre fact has been caused by several different issues: the outdated international system for measuring foreign aid; the war in Ukraine; and leprechaun economics, whereby tax-dodging international corporations artificially inflate our GDP and government revenue.

Usually, when so many problems intersect like this, you should expect a complete failure. But this is the even weirder fact: these different causes have all seemingly balanced out. Even when you adjust for bizarre accounting rules and exclude the ‘foreign aid’ that has never left the country, genuine foreign aid spending has been pretty unaffected.

There’s an episode of The Simpsons where Mr Burns goes for a check-up, and the doctor discovers that he is the sickest man in America, with thousands of diseases—and yet, somehow, the effects of all of them have managed to cancel each other out.

Mr Burns: So, what you’re saying is, I’m indestructible?

Doctor: Oh, no, no: in fact, even a slight breeze could—

Mr Burns (leaving): Indestructible…

Irish Aid is not in quite as bad a state as Mr Burns. A slight breeze will probably not blow it over. But a reduction in corporation tax receipts, a new influx of refugees and asylum seekers, or a populist government might; and those are not black swan risks, but very plausible future outcomes. The government is already aware of some of the problems with how foreign aid is measured. But it can and should go further to change the accounting system for its own foreign aid targets, so that ‘foreign aid’ means foreign aid.

Why foreign aid?

First things first: why care? What does it matter what we spend on foreign aid?

In the first place, it matters because Irish foreign aid spending can save lives. In the face of famine, war, disease, poverty, and ethnic cleansing, it costs relatively little money for the State to provide people with food or shelter or medical treatment that can make the difference between life and death. Some people argue that foreign aid is so wasteful and inefficient as to have a net impact of zero, or close to zero, lives saved; I can't argue the point here, but I think they are wrong, and foreign aid can save lives.

Of course, any government should prioritise its own citizens; that’s only right. But because it costs so much less to save lives in the developing world than it does to provide services in a developed country like Ireland, foreign aid can make a huge difference with only a small portion of the government budget. And even when it is prioritising its own citizens, the government has to take into account the fact that the majority of Irish citizens support overseas aid spending, with 30% wanting to see Ireland’s foreign aid spending increased and 39% wanting it to stay the same.2

How can money spent at home be ‘foreign aid’?

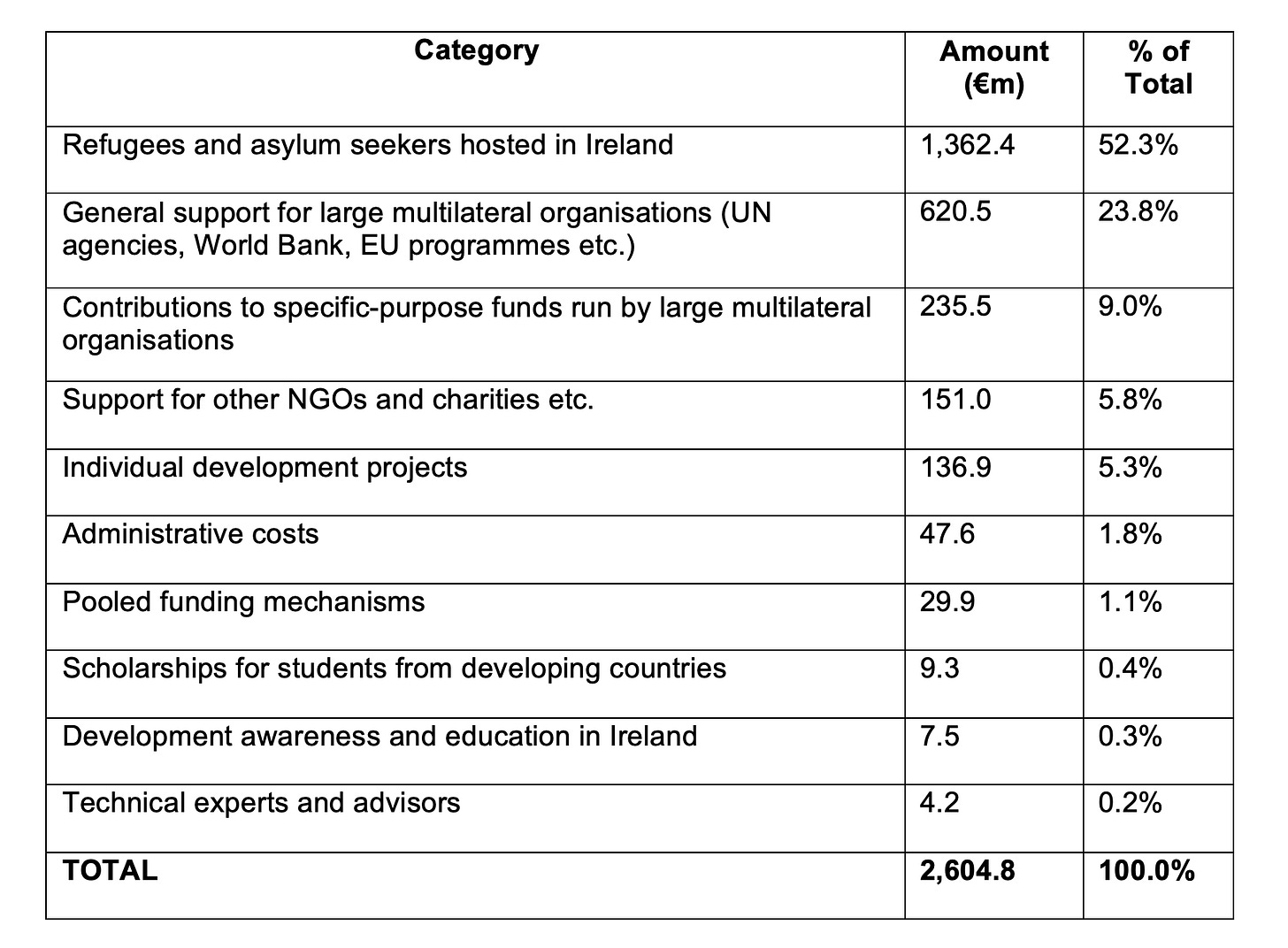

If any of the above is at all convincing to you, you might be quite concerned at just how much of Ireland’s ‘foreign aid’ budget never leaves the country. Of course, some amount always has to be spent on administration, like paying the salaries of people in Ireland who help ensure that our foreign aid is distributed overseas. But that couldn’t possibly account for 55% of all ‘foreign aid’ spending. And, indeed, it doesn’t. The most recent available data that Ireland has reported to the OECD breaks spending down into some big categories:

By far the biggest category of ‘foreign aid’ is spending on refugees and asylum seekers who are already living in Ireland. Refugee spending alone is more than half of all of ‘foreign aid’ spending!

Does this mean that Irish governments have been cooking the books, trying to mislead the OECD and other international bodies into thinking it spends more on foreign aid than it actually does? Not at all. In fact, labelling refugee spending as ‘foreign aid’ is a completely standard practice that international bodies are well aware of. Many countries’ ‘foreign aid’ budgets are actually substantially made up of at-home spending, largely on refugees.

The problem is in the international standard for measuring foreign aid: the OECD’s definition of Official Development Assistance (ODA). This definition explicitly allows governments to report the cost of hosting refugees as part of their foreign aid. Not all money spent by the government on refugees counts as Official Development Assistance: generally, countries are only allowed to claim costs associated with ‘subsistence’ such as food and housing, and only for the first twelve months after the person arrives. But subsistence—especially housing—is still a really significant part of state spending on refugees and asylum seekers, and thus, a really significant part of ‘foreign aid’.3

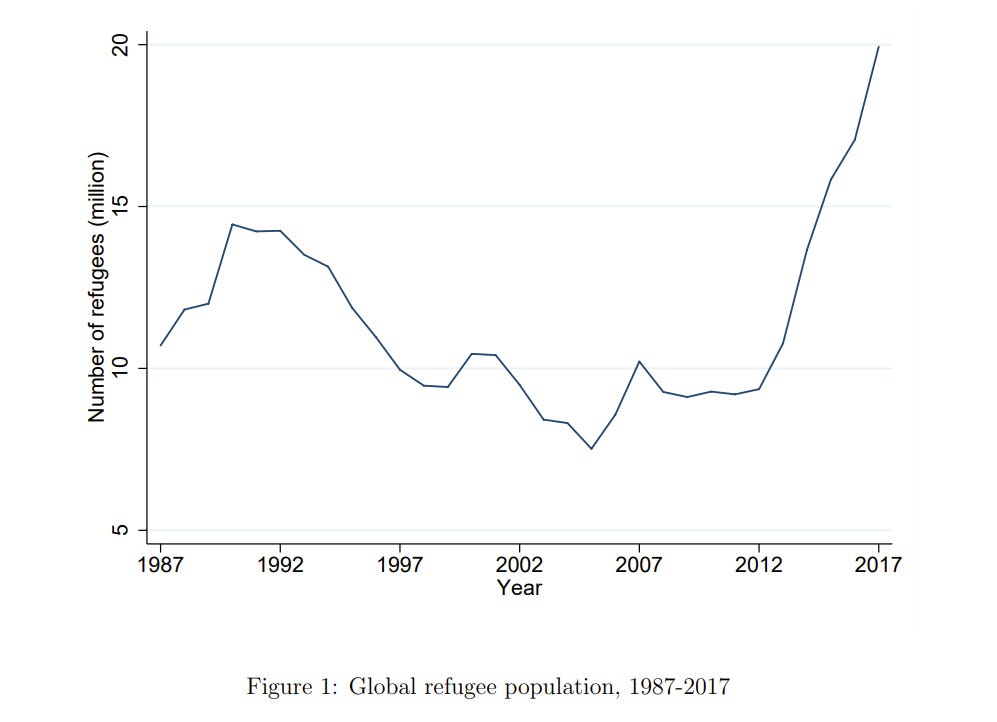

Things haven’t always been this way; the current rules only date from the 1980s. Back then, refugees tended not to flee very far from their home country; as such, given that most refugees come from poorer countries, and poorer countries tend to be near other poorer countries, refugee spending was mostly a problem for the developing world. Rich countries would sometimes provide foreign aid to refugees living in poorer countries, but the small amounts of money they spent on refugees within rich countries were, sensibly, treated differently. It wasn’t until 1988 that the OECD started allowing rich countries to count money they spent on refugees at home, as well as money they sent to poor countries, as ‘foreign aid’.

This never made a huge amount of sense. The rationale was that countries shouldn’t be ‘penalised’ for letting refugees in. But if a rich country’s government redirected some spending from refugees living overseas to refugees living within their own borders, there were no actual penalties; they just couldn’t report it as foreign aid for accounting purposes, because (after all) it literally isn’t foreign aid! Nonetheless, even if it didn’t make much sense, nobody cared that much about the change because it was incredibly minor. The number of refugees living in rich countries was quite low; the rule change was a marginal tweak that didn’t have a meaningful impact on the headline numbers on rich-world foreign aid spending.

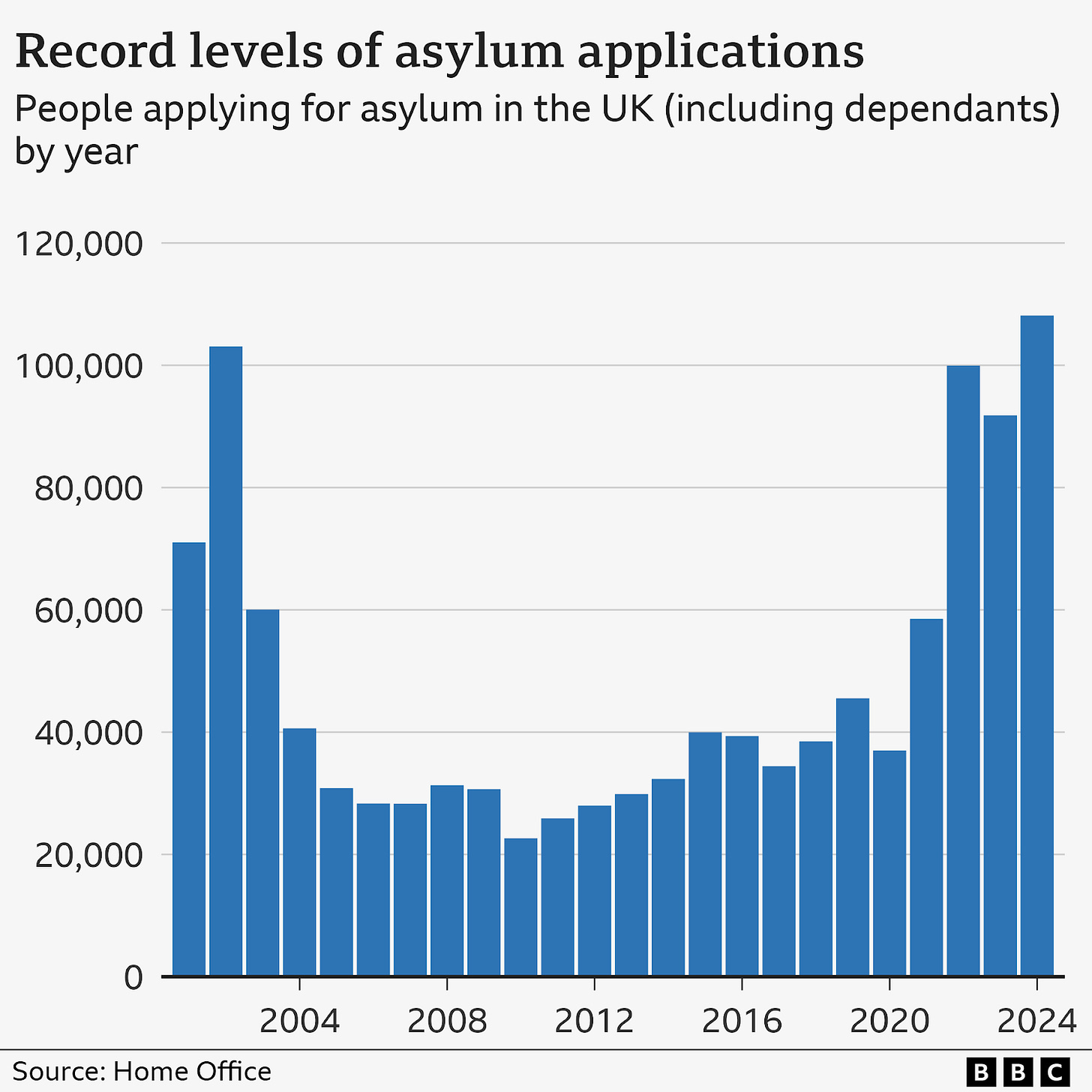

That’s not the world we live in any more. The number of refugees is higher, and a larger proportion of them make their way to rich countries.

The amount of money spent by rich countries on refugees and asylum seekers is no longer marginal; it’s now a central and fiercely debated political issue. An accounting rule that had previously made a barely-perceptible difference has come to hugely distort foreign aid numbers, especially after huge numbers of Ukrainians made their way to rich European nations (like Ireland) in 2022.

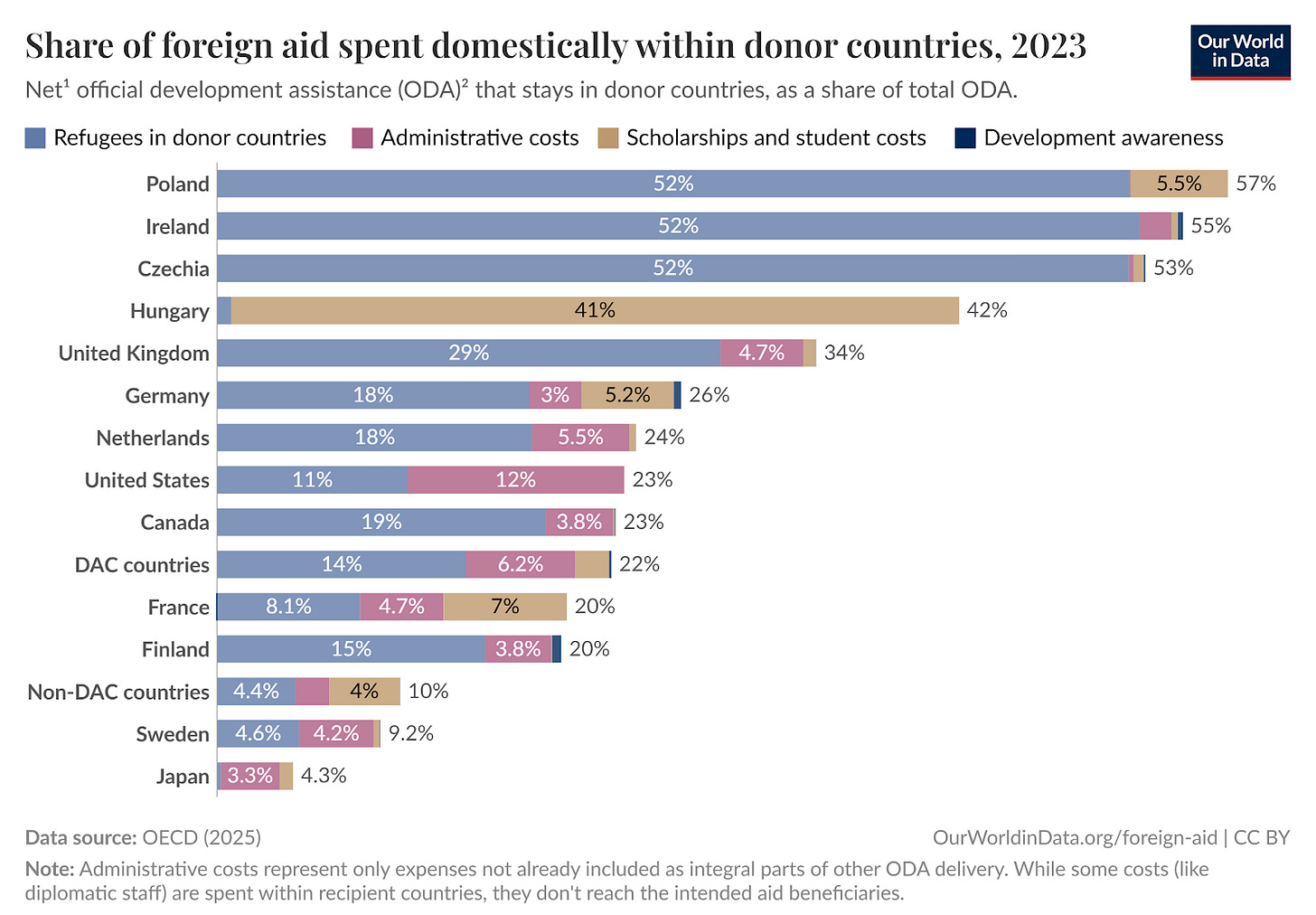

The upshot is that, in 2023, out of every euro spent by rich donor countries on ‘foreign aid’, 22 cents wasn’t foreign aid at all.4 And in some countries, Ireland included, this discrepancy was far worse. It’s not sustainable to ignore this any more.

The ODA accounting rules have perverse consequences

The first problem with the ODA rules is simple. When the Irish government spends money on refugees living in Ireland, that is not foreign aid. That is not what the phrase ‘foreign aid’ means to most people. We should care about the meaning of words; we should care about accurate accounting.

Maybe you think I’m being pedantic. But there are other, more concrete problems.

Above, I highlighted one of the main reasons that rich countries should have foreign aid programmes: it is much cheaper to provide services in poor countries than it is in rich countries, and so even a small proportion of a rich country’s budget can make a huge difference in poor countries. Partly this is because a euro ‘goes further’ overseas because of differences in purchasing power. And partly it’s because rich countries and poor countries tend to face different problems: it is pretty cheap to provide people with polio vaccines; it’s not so cheap to help people who have fallen into homelessness in Dublin.

But neither of these rationales apply to money spent on refugees in Ireland: a euro obviously doesn’t ‘go further’ in Ireland, and the things that refugees and asylum seekers in Ireland need (housing, food, social support) are pretty similar to the things needed by many Irish citizens.

Overseas aid spending doesn’t have to be efficient, but in general it is. Refugee spending at home, by contrast, is no more inherently efficient than any other programme: the number of people helped is much lower, the cost of helping them is much higher, and the amount of budget required will fluctuate wildly over time with refugee flows. If spending on refugees comes to take up more and more of ‘foreign aid’ budgets, then a major part of the rationale for foreign aid spending is undermined.

This comes with political risk. It doesn’t take a great leap of the imagination to think about what would happen to Ireland’s foreign aid budget if a populist, anti-refugee government came to power, having been told that most ‘foreign aid’ was actually disguised spending on refugees and asylum seekers living in Ireland. But this is only the most dramatic scenario.

Ultimately, the real source of risk is that people don’t like feeling like they’re being lied to. And, in this case, Irish citizens kind of are being lied to! The foreign aid accounting standard isn’t intentionally deceptive—nobody’s setting out to lie to the Irish people—our government is just using the standard international definition exactly as intended. But that doesn’t change the fact that citizens who read about ‘foreign aid spending’ are labouring under a serious misapprehension, through no fault of their own.

I can try to imagine an argument against my view. If you think that rich governments should be spending money to support refugees at home, then you might think that folding this spending into ‘foreign aid’ could be a way to protect it from populist backlash, perhaps because rich countries have foreign aid targets and cutting refugee spending would make it harder to reach those targets.

The issue with this analysis is that refugee policy is so salient, and so controversial, that you’re not going to be able to distract people from it with a minor accounting change. And rich countries really don’t care all that much about their foreign aid targets. Tying foreign aid and refugee spending together won’t help save refugee spending; it just puts foreign aid at additional political risk.

And even if I were wrong about this—even if the ODA rules really did incentivise governments to spend more on refugees—this would still give rise to perverse outcomes. Under the ODA rules (as they were clarified in 2017), not all categories of refugee spending can be counted as foreign aid; you can only report money spent on subsistence (food, housing, etc.), and only for the first twelve months after the refugee fled their home. In particular, money spent on programmes to help refugees integrate cannot be declared as foreign aid under the rules. If policymakers were trying to hit their foreign aid targets above all else, this would incentivise them to accept huge numbers of refugees, provide them with basic subsistence for twelve months, but put no effort whatsoever into helping them integrate into society, and then stop supporting them completely after those first twelve months are up. I don’t think anyone, on any part of the political spectrum, wants that.

What is Ireland’s government doing?

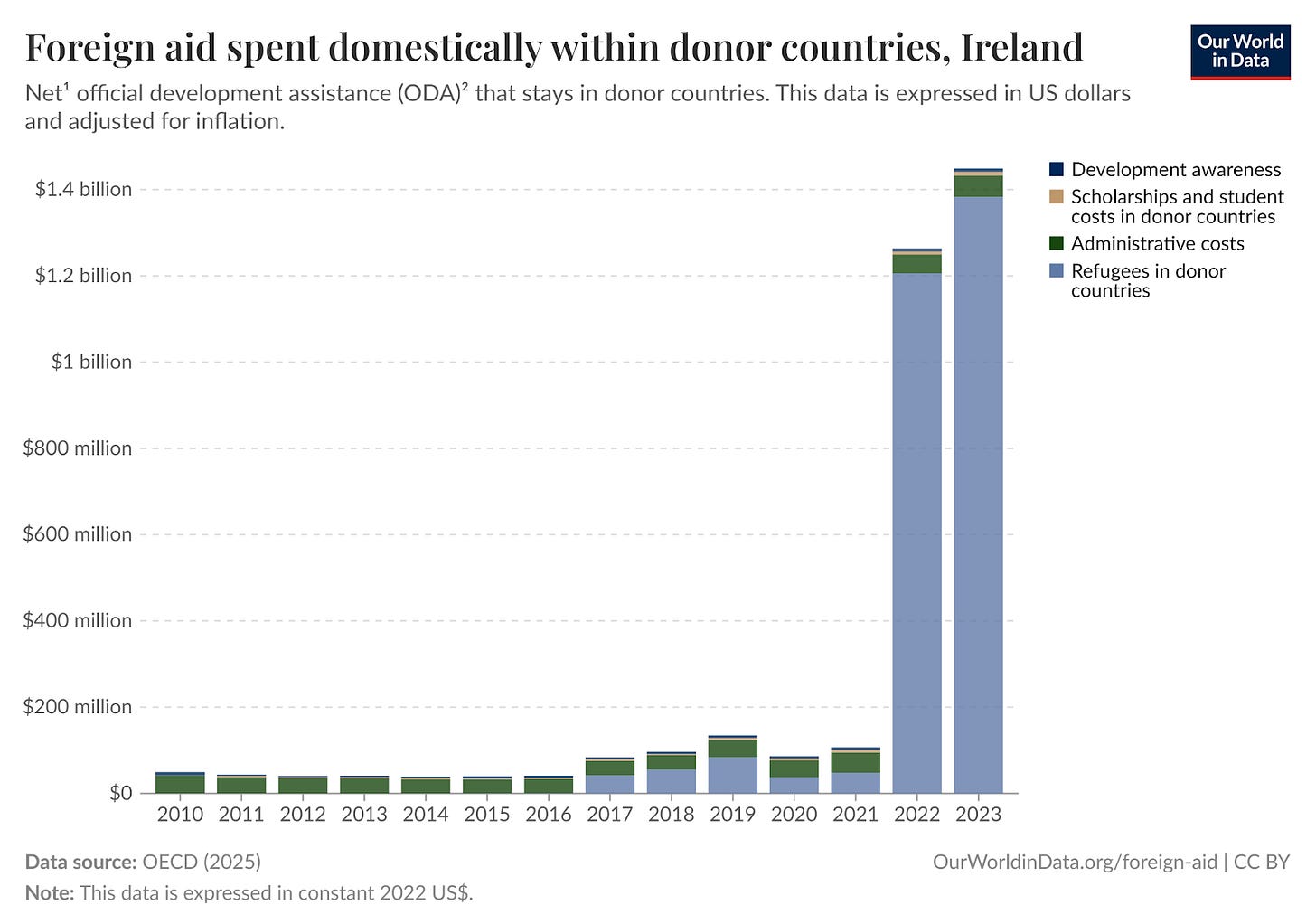

Ireland is in a weird spot relative to all of this. Over the last few years, with the war in Ukraine, the percentage of its aid budget that has been spent on refugees has skyrocketed. In terms of in-country ‘foreign aid’ spending, we are now second only to Poland.

This is not just the result of a large number of Ukrainians coming to Ireland, although that’s a big part of it. 112,000 Ukrainians sought refugee status in Ireland; the highest number per capita of anywhere outside Eastern Europe.5 Ireland also has much higher costs per refugee than any other country, with the exception of the UK. (How costs got quite this high is a story for another day.)

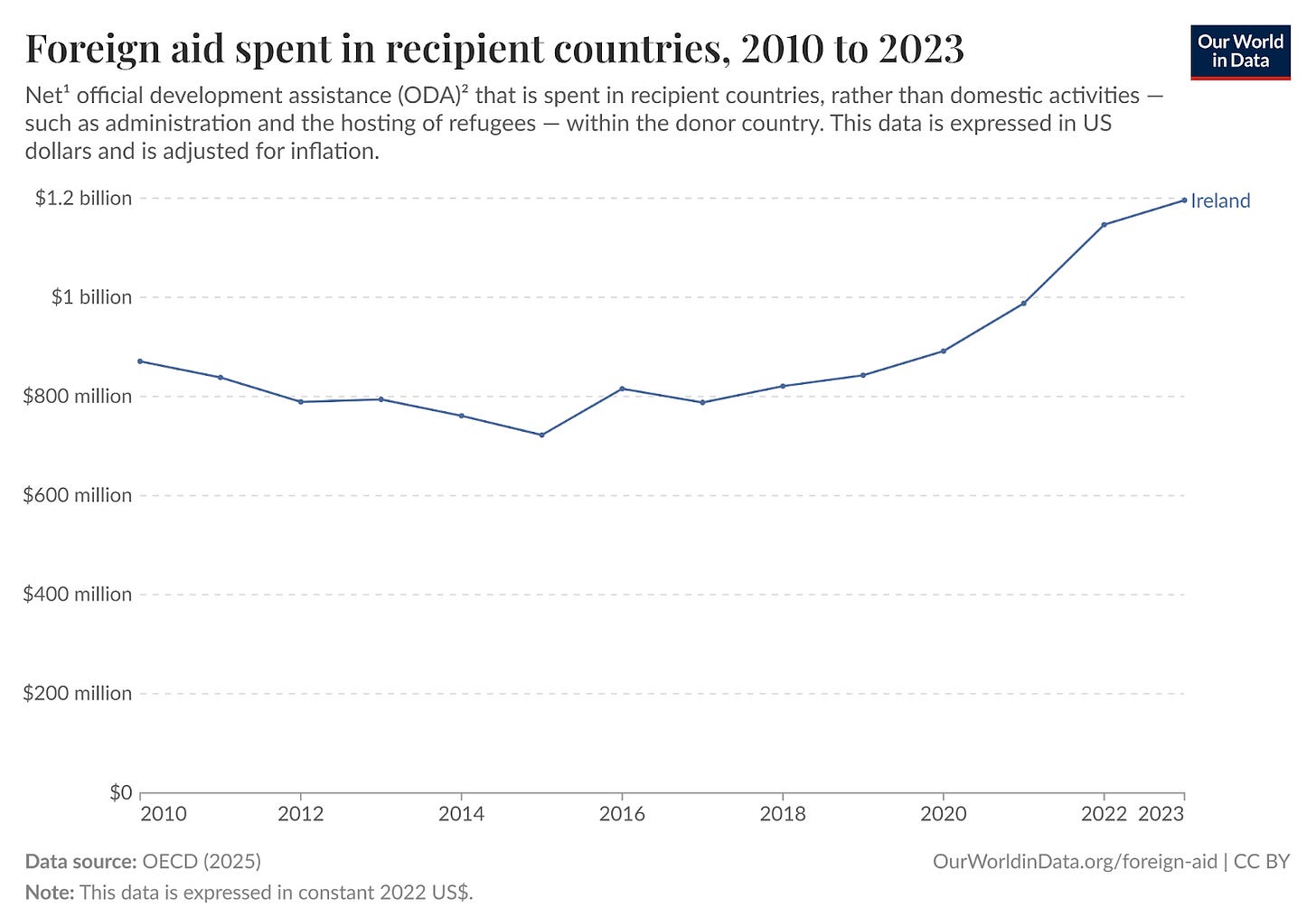

You might expect that there would have been some drastic cuts to the rest of the foreign aid budget to find the money needed to provide for these large numbers of refugees. And yet, if you exclude all the in-country spending and just look at the amount of foreign aid spending that actually leaves the country, it’s actually been exactly the opposite: it’s been going up.

What’s going on here? There’s a simple answer: ‘leprechaun economics’. Ireland’s place as a haven for tax-dodging corporations has distorted our GDP statistics and, relatedly, brought in huge government budget surpluses via corporation tax. The result has been something of a spending bonanza in Ireland recently, as all sorts of different interest groups and campaigners start asking the government for additional funding for their pet projects, and the government—flush with cash—has found it increasingly easy to say yes for quick political wins.

And so, as part of this, many NGOs have been reminding the government of its commitment to eventually spend 0.7% of gross national income on foreign aid.6 And so, additional funding has been allocated to foreign aid over and above the increase in refugee spending. It’s not as much extra spending as the NGOs would ideally like, but it’s more than enough to allow the government to drop a mention of foreign aid into press releases. It’s all a part of the ‘when I have it, I spend it’ mindset that is so prevalent in Ireland.

That the majority of Irish ‘foreign aid’ money is actually spent on refugees and asylum seekers in Ireland is the kind of claim that populist politicians would have a field day with. The tweets write themselves: ‘money that should be saving lives in the third world is being used to put foreigners up in Dublin hotels!’. Although it sounds outrageous, this claim is entirely factually true. But dig a little deeper, and Irish foreign aid is on a materially better footing now than it was several years ago. The issue is primarily a data classification problem.

Like with Mr Burns, Ireland has caught a whole load of diseases: not just the terrible ODA accounting rules, but also the war in Ukraine, a consequent large number of refugees requiring state support, a higher cost-per-refugee than any other EU country, an economy that has been significantly distorted by multinationals looking to avoid tax, and politicians with bad spending habits. And yet, somehow, when it comes to foreign aid, all the errors have managed to cancel each other out.

The worry is just that, like with Mr Burns, our blind luck is misinterpreted and used as the grounds for complacency. Data classification problems are still problems.

The UK: a warning

Our next-door neighbours are an example of how things might go wrong with foreign aid.

British politicians also have terrible habits when it comes to fiscal policy. But unlike in Ireland, there’s no ‘cushion’ of corporation tax receipts; indeed, there’s been barely any economic growth at all over the last twenty years. And so, international investors have become increasingly concerned about the long-term outlook of lending money to Britain, and British governments have found themselves ‘boxed in’ by high borrowing costs.

Into this context came a large number of refugees and asylum seekers, starting in 2022, which placed further pressure on British government budgets in order to provide for them.

In this situation, the temptation for any policymaker who has heard about the ODA rules is obvious: why not just take money from existing foreign aid budgets to fund refugee spending? After all, announcing a cut to any other area of government spending to free up money for refugees is politically explosive. But if you use the money allocated to aid, you won’t even have to announce a cut. Maybe the few wonky think tanks and blogs that actually understand the accounting rules will figure out what you’ve done and get upset, but that’s it.

And in fact, this is exactly what the UK did. In recent years, British governments have taken the approach of reporting ‘anything that could possibly be reported’ under the ODA rules (without increasing foreign aid budgets in tandem) as a way to quietly redirect money. And while wonky think tanks and government watchdogs did indeed complain, the change otherwise slipped under the radar. It wasn’t until February 2025, when the government announced a cut to the overall ODA budget (including refugee costs), that the press or public noticed anything. But by that point, the amount of ‘foreign aid’ money that was actually leaving the country and being spent on development projects overseas had been declining significantly for years.

This is bad because foreign aid is good, and cuts to foreign aid cost lives. But it’s also bad because the UK’s unclear and opaque accounting practices have encouraged waste and inefficiency, undermining the whole purpose of this approach. For example: one part of the UK Government, the Home Office, has most of the responsibility for refugees and asylum seekers; but insofar as its spending can be reported as ‘foreign aid’, it can claim that money back from a different part of the government (the Foreign Office). This encourages officials in the Home Office, not to spend money efficiently, but to spend money in a way that allows them to report as much of it as foreign aid as possible. ‘Gaming the system’ like this has been a contributor to ballooning refugee costs.

In turn, when a government’s approach to foreign aid is to cut it as quietly as possible, this doesn’t naturally lead them to eliminate the least efficient or most wasteful programmes first. Instead, they’ll prioritise cutting the ones that will involve the least political confrontation. But this means that the simplest programmes with the fewest ‘stakeholders’ are often the first to go, and these can be the most efficient. Recent reporting suggests that, even as the UK has cut back on foreign aid, there are still plenty of wasteful projects receiving funding.

What next?

Ireland has, thus far, avoided this trap. The amount of genuine foreign aid has grown. To safeguard this, recent budgets have explicitly allocated most of this increased funding directly to the Department of Foreign Affairs, ensuring that it can’t easily be redirected to at-home spending. Irish Aid has even begun to separate out costs associated with Ukrainian refugees when talking about foreign aid spending. All of this should be commended; the eye-catching fact that most Irish foreign aid never leaves the country isn’t as worrying as it might seem.

But if spending on refugees and asylum seekers continues to grow, future governments may be tempted by the example of the UK and other countries, and exploit ‘creative accounting’ to de facto cut foreign aid as refugee costs rise. Alternatively, a populist government may use the high proportion of foreign aid that’s spent on refugees as an excuse to scrap the lot, perhaps inspired by the American example of DOGE. And given the threat posed by Trump’s tariffs to Ireland’s economic model, all types of government spending face political disruption over the next few years.

The simplest option is for Ireland to improve its accounting practices by following the approach taken by countries like Australia: just don’t report in-country refugee spending as ‘official development assistance’. Just because the government can report this money under ODA rules, doesn’t mean it has to; not all countries’ governments do.

This unilateral approach comes with some downsides, though. The nerdy complaint is that it makes international statistics which compare different countries less apples-to-apples, and so makes life harder for researchers. An issue that is more likely to prick policymakers’ ears is that this unilateral approach might make Ireland look worse: if we take a principled stand, but other countries don’t, we’d drop down the international rankings in foreign aid spending. We’d do a good thing, but look less generous because of it.

A different approach would be to build on the existing practice of separating out Ukrainian refugee costs, by separating out all in-country aid spending (or all except administrative costs and the like) when the government talks about its foreign aid budget. The government could still report the full amount to the OECD, to make sure that Ireland is treated fairly in international comparisons; but when compiling accounts, sending out press releases, and allocating budgets between departments, it should impose a strict distinction.

This kind of self-imposed discipline is hard for governments to stick to. So I will make a final suggestion that might help Ireland’s government stick to it. The government is aiming to meet the UN target of spending 0.7% of GNI on foreign aid, as defined by the ODA rules. Even when governments aren’t on track to meet their targets (and they rarely are), the targets still play an important role in policymaking, because they define the metrics that governments use to see how far short they’ve fallen and how much their policies are making a difference.

The government should therefore, on top of the existing UN target, set itself a target for the amount of foreign aid that Ireland actually spends overseas, excluding in-country spending.7 The exact level of this target will inevitably become a matter of haggling and political contestation, but if the government were smart about it, it might not require any changes to spending plans in the short term.

Ultimately, the number that is being targeted matters less than the fact that the target exists. Merely having a target will require the government to make an honest accounting of foreign aid, excluding refugee costs and other in-country expenses. This will keep future governments from being tempted to shuffle money around, quietly cutting foreign aid de facto without announcing any cuts. It will keep us away from the waste and inefficiency that have resulted from the UK’s attempts to game the system. And, ultimately, it’s just more honest. When the public hears ‘foreign aid’, they expect that it means foreign aid: money spent overseas to help people in need. They’re not stupid for thinking that. The government should respect that.

Peter McLaughlin is associate editor of The Fitzwilliam and an Emergent Ventures winner. He writes the blog Her Fingers Bloomed. You can email him at peter [at] thefitzwilliam [dot] com.

All statistics, where not otherwise sourced, are taken from the excellent Our World in Data, whose work on foreign aid I relied heavily on when researching this post.

I am a little sceptical of the source for these numbers, which is the Dóchas annual tracker survey. The questions in the survey remind me of that bit from Yes, Minister, starting by prompting people on their concern about international poverty before going on to ask them about whether aid should be increased. But they are the best numbers available. And certainly, these figures show that support for foreign aid in Ireland is much higher than it is in other countries (compare the UK numbers, e.g. here). Some of this difference might be down to the way Dóchas designed its poll, but the difference is so big that I don’t think that’s all that’s going on: probably there is a real difference in public opinion, with more support for foreign aid in Ireland than in other comparable countries.

In this post, when I write about ‘refugees’, I am usually also including those who have not yet been granted ‘refugee’ status but have applied to be granted it. These people are normally called ‘asylum seekers’, and distinguished from refugees, as some asylum seekers will be deemed not to count as refugees and will have their claims denied. The reason I don’t distinguish between the two groups in this piece is because the ODA rules don’t make any distinction here, and treat ‘refugees’ and ‘asylum seekers’ alike—a further source of confusion.

ODA operates with a significant time lag; the data from 2024 is still preliminary, and I won’t consider it in this piece.

Sam Enright for Progress Ireland recently wrote about the 0.7% foreign aid spending target in the context of whether a similar target might work for government support of research and development. His piece also touched on the strange and unscientific origins of the 0.7% target, which Michael Clemens and Todd Moss have written about in more detail here.

Again, things like administrative costs might reasonably be treated differently from other types of in-country spending, since they do relate to genuine foreign aid even if the money is spent in Ireland. But these are a small category regardless. The government might also take the opportunity to set the target in terms of GNI*, the adjusted metric that best suits Ireland’s unique economic situation, rather than GNI which the UN target uses.

Seems perfectly reasonable to me for foreign aid calculations to include giving aid to foreingers.